Shortly after his election in 2016, polling surveys put President Duterte’s trust rating among Filipinos at 91 percent. One commenter observed “it seems he has the pulse of his nation.” But as a politician whose unusually transparent temper has been a cause of concern when it comes to American-Filipino affairs, how steady is that pulse? As President Biden and his Administration have settled in at the White House, clearing their first 100 days in office, it is time to check in on the relationship between the United States’ former Vice President and the former Mayor of Davao, and what we might expect from their relations as presidents and proxies for their respective countries. To do so will also require the context of the rollercoaster ride that is the last 5 years with Duterte, Obama, and Trump.

Duterte and Obama

Although their time in office overlapped for less than a year, the two executives had a rough go of it. Obama was quick to challenge Duterte’s drug enforcement agenda. Duterte, after insulting US Ambassador Philip Goldberg with a homophobic slur, replied by addressing Obama specifically with misogynistic comments and telling him to “go to hell” while threatening a “break-up.” In response, Obama cancelled their scheduled summit meeting. This was a low point for diplomatic relations, and was contradicted by statements from wingman Defense Secretary Carter that US-Philippine ties were “ironclad,” despite Duterte expressing his fancy for Russia or China. But with the approaching 2016 US election, Duterte didn’t have to wait long for his ideal presidential partner to come along.

Duterte and Trump

Rising to power as one of this era’s global “strongmen,” Duterte found a kindred spirit in the authoritarian, nationalist leadership of Donald Trump. Countless writers have pointed out the similarities shared by the two men, from their populism to their political aesthetics. But even with these common features of the Filipino Trump and the American Duterte, it was not clear from the outset, should the two could get along,that their represented countries would benefit from the close relationship. Indeed, after their first phone call together, Duterte rejected Trump’s invitation to come to the White House in tandem with an upcoming hosted ASEAN meeting. However, things began to smooth out for Duterte and Trump over the next four years, with highlights like Trump showering compliments while skirting human rights issues, and Duterte singing a literal serenade at the order of the Commander-in-Chief. For this pair, it was not ‘opposites attract’, but rather cutting from the same cloth that made for a perfect match. And ironically, their bond did seem to renew commitments between the Philippines and the US. In 2018, Philippines Ambassador Jose Romualdez articulated this sentiment in a lecture delivered at BYU, titled The Philippines and the US: An Enduring Alliance. Speaking of how the Philippines wishes to extend their hand as an equal, showing the developing balance from the negative relations of Duterte-Obama to the positive interactions of Duterte-Trump, he remarked “we have shared values, shared history, and a shared friendship…We do appreciate the United States, and we want you to appreciate us as well.”

This does not mean the Trump years were without bumps along the way. Issues like the Balangiga Bells, the cancelled visa of Philippines Senator Dela Rosa, and the Visiting Forces Agreement all tested the growing relationship, but eventually yielded to the enduring alliance. When Trump was diagnosed with COVID-19, Duterte was loyal and ready to offer his well-wishes for a speedy recovery. But the ultimate trial of Duterte’s favor towards the US was still to come, when Trump lost reelection in 2020.

Duterte and Biden

Unlike Trump, Biden did not receive a congratulatory phone call from Duterte upon securing the victory in the 2020 presidential election. It is unclear whether this symbolic gesture, or lack thereof, is a result of Trump’s relentless and false allegations of election fraud, leftover animosity from the Obama years rekindled by Obama’s VP becoming President, or hesitancy about the next stage of American involvement abroad under a progressive administration. But Duterte has sent his congrats through official channels, and the President’s spokesperson is confident that the two will quickly become friends. Unfortunately, the timer on Biden and Duterte’s friendship continues to run on increasing pressure from ongoing activity in the region and in political spaces. For Biden and Duterte to make it work, it is going to be complicated.

Regardless of the unconventional relations between Duterte and recent US presidents, much of the conduct of the President of the Philippines in his first six year term is no laughing matter. Worst of which is the extrajudicial killings authorized and encouraged by the President in his speech and public policies implemented in pursuit of the continued War on Drugs. Included among the alarming body count is the death of 61 lawyers, killed since 2016 during the tenure of the Duterte administration. The Biden administration will have to reckon with the fact that associating with Duterte might lead to a tacit (or explicit) condoning of his actions (ala Trump), or loss of influence when denouncing his methods (ala Obama). Perhaps Biden can chart a middle course that decries human rights violations without estranging the Philippines leadership and weakening their hold on the region. Or Duterte could outright reject further American involvement in the Philippine archipelago. No doubt, the US certainly has its own list of abuses and injustices executed against the Philippines as a former colony, a deserving topic for another article. But in 2021, the Philippines and the United States are in a position to determine, should Duterte and Biden find this relationship to be one worth keeping, how to reflect that commitment in their domestic and foreign policy.

In October of last year, US Ambassador Sung Kim bid farewell to his Philippines post. A rumoured replacement was denied by the US embassy back in 2019, and recent suggestions that a nominee was to be named in January of this year have gone unmet. As it stands, the post is empty, temporarily filled by the Charge d’Affaires John Law. Although this period may not be atypical by State Department averages, it muddies the water on Biden’s stance towards diplomacy with Duterte. It is also a terrible time to be missing an official Ambassador to the Philippines.

Just three weeks ago, the International Law and Policy Brief posted a piece by Ha Huynh explaining the conflict and complexity arising in the South China Sea, both in terms of international law claims and military presence. I refer the reader to that detailed discussion, but to briefly summarize – China continues to make aggressive advances into the legal gray areas of the oceanic territory south of the Asian mainland. Duterte has already indicated that he will not withdraw vessels deployed in the contested waters, in a surprising defiance of Chinese intimidation. By virtue of its alliance and interest in the Philippines and other SouthEast Asian countries, this pushes the US to an even greater conflict with China, leading a minority of voices to question the merits of American commitments in the region. The Biden administration has responded affirmatively to the need for support of the Philippines in this scenario with rhetoric, resources, and readying of combat groups.

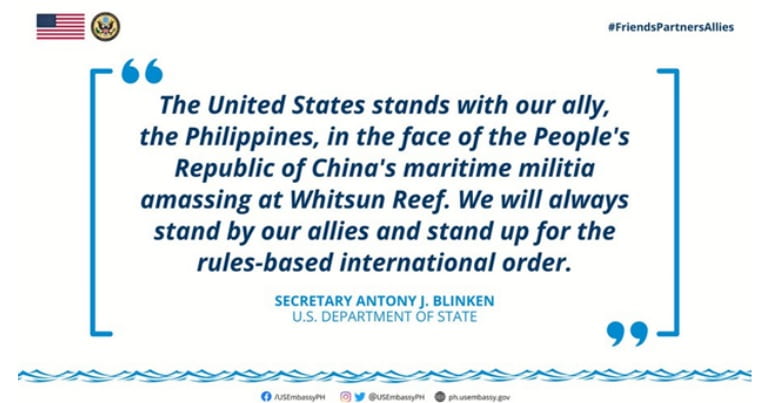

US Secretary of State Blinken quickly vocalized the President’s broad support in standing firm with the Philippines.

This message has been broadcast loud and clear on all channels, and collaboration between US National Security Advisor Sullivan and National Security Advisor Esperon of the Philippines has begun to make good on that word. In March, US officials executed a hand-off of 3.7 million PHP worth of equipment to aid the Philippines in maritime law enforcement, and April brought the integration of the Roosevelt Strike Group and the Makin Island Amphibious Group for conducted operations in the South China Sea.

In closing, as the US and the Philippines celebrate 75 years of alliance and diplomatic relations, there is a need for clarity in the standing of future American-Filipino affairs. The lack of a formal ambassador and vague absence of any nominee, juxtaposing the unambiguous US backing of the Philippines in the South China Sea, leaves an unclear picture of what the next few years will look like for the two countries. The public and official acts on the part of Biden do seem to indicate that he is invested in the ongoing alliance. It remains to be seen how Duterte, a figurehead for whom American presidents have failed and succeeded to productively interact with, will personally engage with Biden, or if he will reciprocate the effort.

Author Biography: Garrett May is a moderator for the International Law and Policy Brief (ILPB) and a J.D. candidate at The George Washington University Law School. May received a B.A. in Interdisciplinary Humanities with an emphasis in History and a double minor in Asian Studies and Linguistics from Brigham Young University in 2020. Prior to attending law school he lived in the Philippines for two years. His primary field of interest is immigration law.