Lin Qiming, a Chinese state security agent, had several creative suggestions for how to destroy Yan Xiong’s nascent congressional campaign in the Democratic primary for New York’s 10th District. In Mr. Lin’s conversations with a private investigator (PI) he had hired to follow Mr. Yan, Mr. Lin initially suggested that the PI find something scandalous in Mr. Yan’s past. The price, he assured the PI, did not matter – as long as Mr. Yan’s campaign cratered. When the search for scandals in Mr. Yan’s past proved fruitless, Mr. Lin proposed that the PI create a nonexistent one, helpfully providing ideas that included “child porn” and “homosexual activity.” Gradually, Mr. Lin’s entreaties became more desperate. As a last resort, would the PI consider beating up Mr. Yan? Perhaps a car accident to take him out of the running?

The details above, divulged by an FBI agent in litigation against Mr. Lin, seem unbelievable. Why would the powerful Chinese state involve itself in a smear campaign – and potential violence – against a candidate who garnered a paltry 1.1% of the vote in the Democratic primary? The answer: Because Mr. Yan is a Chinese-born dissident who led student protests against the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in the 1989 Tiananmen Square Uprising. After seeking refuge in the United States, he joined the U.S. army and has remained a steadfast critic of China. For example, in an interview with the New York Post given during his campaign, Mr. Yan explained: “In China, I was a freedom fighter. I joined the Army when I came to America because I wanted to be a freedom defender.”

Although the general public in the United States may associate other countries, like Russia and Iran, with mounting election misinformation campaigns, China is stepping up its efforts to interfere in U.S. politics. Most of its attempts are more subtle than the bizarre incident detailed above. While its information operations are not yet as advanced as those of some other nations, the communist state is a force to be reckoned with and should not be underestimated.

Disinformation and Social Media Campaigns

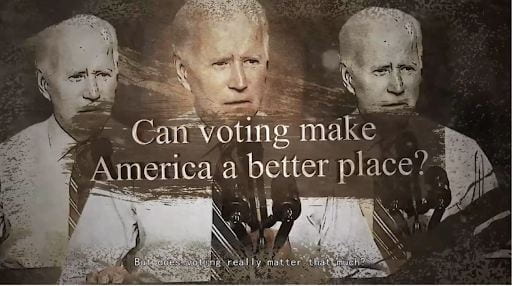

The image accompanying this article is a still from a video associated with Dragonbridge, a CCP-affiliated propaganda operation. In the video, a disembodied English-speaking voice claims that voting in U.S. elections is pointless. As the video shows images of the January 6 insurrection, the voice laments Congress’s ineffectiveness and the small ratio of bills introduced that ultimately become law. The solution to the U.S.’s political ills, the voice urges, is for Americans to get rid of the entire democratic system. Ominously, Dragonbridge-affiliated content has called for violence against law enforcement.

Typical Dragonbridge exploits involve spreading negative falsehoods about the United States, such as blaming the U.S. government for explosions caused by gas leaks on the Nord Stream 2 pipeline and implausibly alleging that COVID-19 originated in Maryland. However, the minds behind Dragonbridge have also attempted to cause a real protest in New York. In April 2021, thousands of accounts associated with Dragonbridge began promoting a rally to protest the “rumor,” spread by some U.S. government figures and Chinese dissidents, that COVID-19 began in a Chinese lab (a recent Senate report from the minority staff of the Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions concludes that this theory is more likely than not to be true).

It is unclear whether anyone actually showed up to the protest. Luckily for the U.S. government, it does not appear that many real Facebook and Twitter users actually consume Dragonbridge’s content. Many Dragonbridge-associated social media accounts are sloppily constructed, with stock-image profile pictures and usernames consisting of long strings of numbers after a random English name. The posts themselves often contain numerous grammatical errors and hashtags in both English and Chinese. Nonetheless, the number of CCP-associated accounts involved in information operations is impressive. In late October, Twitter cracked down on over 2,000 fake Chinese accounts that were posting about U.S. elections being rigged. A month earlier, Meta (Facebook’s parent company) removed numerous fake accounts originating in China that also frequently posted about the United States, criticizing U.S. President Joseph Biden for corruption and Senator Marco Rubio for being insufficiently supportive of abortion access.

Fake Dragonbridge-associated accounts are unlikely to be taken down, however, on Chinese platforms like Douyin, China’s equivalent of TikTok, and TikTok itself. Both platforms are owned by the same Chinese parent company, ByteDance. Dragonbridge is far more successful on these platforms. On Douyin and TikTok, Dragonbridge-associated videos garner between hundreds and thousands of likes. The most successful videos tend to amplify criticism of the United States that comes from real sources, such as a clip of Senator Bernie Sanders listing allegedly U.S.-backed foreign coups and an interview with former Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard discussing the possibility of China and Russia becoming the world’s policemen if the United States takes a less active role in world affairs.

Hacking

While China’s social media misinformation and election interference campaigns are somewhat amateurish, its hacking capabilities and operations are anything but. According to the FBI, hackers affiliated with the CCP have been scanning the websites of the Democratic and Republican parties to identify vulnerabilities. In recent months, FBI agents have quietly warned state Republican and Democratic party offices that they might be targets of Chinese hackers.

The hackers’ objective might just be simple information gathering. Clearly, they want to know more about political candidates, political parties, senior government officials, and the staffs of all the above. But there might be a more sinister reason for their interest in this information: according to a report from the National Counterintelligence and Security Center, the Chinese government is interested in using U.S. state and local leaders to promote pro-Chinese propaganda and stifle criticism of the CCP’s policies towards Taiwan, Tibet, and the Uyghur ethnic minority. In 2020, a Chinese diplomat tried to manipulate a state senator into introducing a resolution praising China’s COVID-19 mitigation efforts, which include large-scale digital surveillance of Chinese citizens. By weaponizing information gleaned from cyberattacks on political targets, China’s next influence campaign on a state senator could be successful.

While none of the targets in this election cycle appear to have actually been hacked, China’s hackers have been more successful in the past. In 2008, hackers associated with the Chinese government successfully penetrated the Obama and McCain campaigns’ computer networks, apparently looking for information on the candidates’ China policies. This history suggests that the CCP is more than capable of interfering in elections if it wishes to.

Conclusion

China has not yet built up a sophisticated election interference infrastructure, but the U.S. national security community should still be wary. In just a few years, relations between China and the United States have deteriorated sharply. While Russia and Iran have more sophisticated information operations, China’s has gone from nonexistent to a formidable force in the last few years. The advanced nature of its hacking operations shows that the CCP should not be underestimated.

Author Biography: Katherine Dolgenos is a Moderator of the International Law Society’s International Law and Policy Brief (ILPB) and a J.D. candidate at the George Washington University Law School. She has a B.A. in Politics from Pomona College. Tweet