Do universal human rights exist?

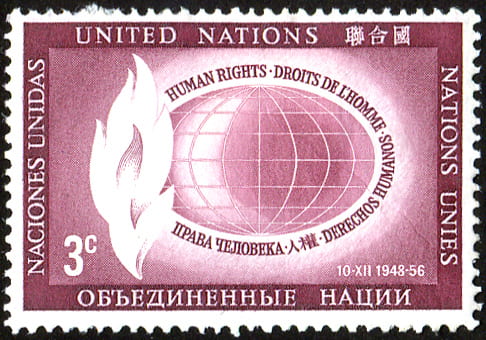

In 1948 the world was tired. It had suffered through back-to-back world wars and an increasing rise in globalism led the world’s nations toward a unified goal: Peace and international unity. This newfound internationalism led to the creation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), a codification of customary international law with regards to human rights. The committe that helped draft the UDHR included a Catholic, a Confucian, a Zionist, and a member of the Arab league. This hodge-podge of individuals managed to construct a declaration that promoted civil and economic rights—and the world was on board too. Forty-eight nations voted in favor of the declaration and zero nations voted against adopting the declaration, a significant consensus at the time. It seemed as if, on a globe filled with diverse values, the countries of the world had found their common-denominator.

Since the drafting of the UDHR, a multitude of globally altering events have occurred. There are now an additional 135 members in the UN. China has transitioned from a fledgling republic to an authoritarian powerhouse. The Soviet Union has disintegrated. And the US has gone from being the world’s sole superpower to being on the cusp of losing that honor. It now seems that the international system is far away from where it once was. Now, the world is weary of internationalism. The UK has fled from the European Union. China is on a mission to make the sovereignty of the nation-state popular again. Even the US, regarded as the primary protector of the liberal world order, has found bipartisan support for protectionism, despite being deeply polarized internally. This evolving international political landscape necessitates a reevaluation of the UDHR: Is there still international support for the UDHR? And if not, what is necessary to ensure the international community respects the universal human rights norms that there are?

Does the World Support the UDHR?

It is hard to envision an attempt to draft an all-encompassing universal declaration of human rights succeeding today. This is because states do not adhere to the current declaration. However, before delving into adherence to the UDHR, one must understand the UDHR’s idealistic contents.

UDHR rights can be placed into three categories. First, there are rights of the individual toward the community (Articles 12-17), including freedom of movement, a right to seek asylum, a right to nationality, a right to marriage, and a right to property. Second, there are civil rights, such as the freedoms of conscience and expression (Articles 3-5, 18-21). Finally, there are economic rights, including a right to an adequate standard of living (Articles 22-27).

After considering this wide breadth of rights, one must acknowledge the reality that countries do not observe all of these rights with exact reverence. Recently, countries have put the broadness of the freedom of movement clause into question by imposing international travel restrictions to combat COVID-19. China has demonstrated its reservations on civil rights with its censorship of media and reeducation camps for Uighur Muslims. Additionally, there is debate on the legitimacy of economic rights. For example, the argument of whether there is a right to healthcare persists in the US. These situations show hesitancy toward the UDHR’s enumerated rights among its member states. This begs the question: Why are states hesitant toward adherence to the UDHR?

One source of hesitation has come from disputes over the religious nature of the UDHR’s rights. Some argue that the UDHR relies too much on religious principles such as the concept of natural rights, which finds its ties in Christian traditions. Thus, critics may find current conceptions of human rights too heavily tied to religious traditions. On the other hand, there are critics that argue that religion is not considered enough in international human rights standards. Iranian diplomat Rajaie-Khorassani expressed that the UDHR was “a secular understanding of the Judeo-Christian tradition”, which compromised Islamic law. Thus, non-Judeo-Christian countries, like Iran, may use religion to justify their reservations to the UDHR.

Another source of criticism comes from those who delineate the differences between Eastern and Western conceptions of human rights. Singapore’s founding father, Lee Kwan Yew, emphasized the differences between Asian and Western values, noting that Asian values focus on communal rights as opposed to traditionally Western individual rights. Leaders outside of Asia have expanded Lee Kwan’s Yew’s conceptions of Asian values into their own sphere, such as Rwanda’s Paul Kagame who has sought to model his nation after Singapore’s more communal system. Chinese leaders further support the idea that Western and Eastern conceptions of human rights differ, stating that human rights should be centered around providing stability and order, rather than providing individual protections. Thus, skepticism toward UDHR-based rights may find roots in disputes over Eastern and Western values.

Ensuring Universal Human Rights Norms in the Future

Just because some may be skeptical of the current UDHR does not mean they are skeptical of international human rights norms altogether. In fact, there is a general consensus that universal human rights norms are necessary. Skepticism appears to be more concentrated on what are considered human rights, rather than if human rights exist.

In order to answer the question of what are human rights, one must answer the question of how to define human rights. Creating a methodology for defining human rights may help countries to feel that there is an objective process in determining human rights. As a result, countries can feel that international human rights norms truly reflect universal values.

One method in establishing human rights norms is seeing if certain rights fall under the principle of the Golden Rule. The general idea of the rule is that person A should treat person B in the way that person A would want to be treated. One can find a version of this principle in virtually every culture on earth. The principle’s universality makes it a good framework on which to establish human rights norms. However, questions remain on how to use this principle in practice. For example, it may not be wise for a Norwegian to treat a Nigerian according to the Norwegian’s culturally different preferences. As well, using the Golden Rule may better serve as a guide for recommended moral deeds, rather than serving as a method for defining rights, which are, in essence, bare minimum protections. Thus, even the Golden Rule does not serve as a perfect method.

However, using the Golden Rule as an aid, rather than an absolute guide, may facilitate defining international human rights norms. If individuals across the globe collaborate to define human rights standards with a shared principle, such as the Golden Rule, in mind, they could more easily find things which they whole-heartedly agree are rights. Perhaps, they would find that most, if not all, of the UDHR rights pass the test when considering a shared principle, like the Golden Rule. However, such a process could give more legitimacy to such rights, and that legitimacy could help temper skepticism toward such rights norms.

Author Biography: Zach Burgoyne is a moderator of the International Law Society’s International Law and Policy Brief (ILPD) and a J.D. candidate at The George Washington University Law School. He has a Bachelor’s Degree in French and a minor in Political Science from Brigham Young University.