Background on Title 42

Since March of 2020, the U.S. government has used a statute of the Public Health Code to expel over 1.7 million noncitizens from the United States. The Trump Administration utilized a statute from the 1944 Public Health Service Act to implement these expulsions that had never before been invoked in order to change border proceedings during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Typically, expulsions from the United States occur under Title 8 proceedings of the immigration code. However, many of them now occur pursuant to Section 265 of Title 42, which allows the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) to “suspend the entry” of noncitizens into U.S. borders when there is a risk of introducing a communicable disease into the country. This “suspension of entry” functionally works the same as deportation for non-citizens who arrive at the border or ports of entry, but without any of the Title 8 procedures, safeguards, or opportunities for relief involved.

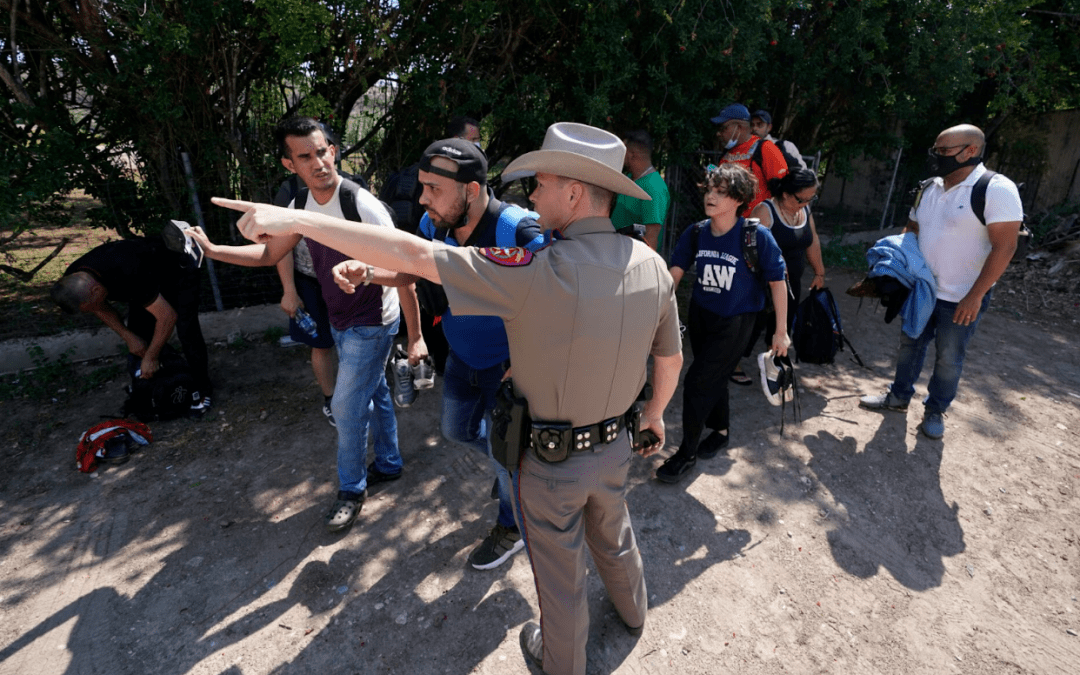

The text of Section 265, however, contains only 128 words. It makes no reference to the humanitarian aid and obligations to which Title 8 adheres. For example, the Immigration Code contains complex asylum procedures for individuals fleeing persecution in their home countries. To replace these proceedings, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (“CBP”) released a four page memo, titled Operation Capio, to instruct border protection officers on procedures at U.S. borders and ports of entry. Operation Capio tells border protection officers to divide incoming non-citizens into deportable and non-deportable categories and to immediately return “deportable” non-citizens to the border or ports of entry. The officers can make these determinations at their own discretion, based on “training, experience, physical observation, technology, questioning and other considerations,” but perhaps most notably, no legal or humanitarian considerations are mentioned.

Background on Asylum

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, an individual arriving at a U.S. border or port of entry could receive humanitarian protection in the United States by applying for asylum. If that noncitizen could prove a well-founded fear of persecution, the individual could become a refugee with lawful status in the United States. As of March 2020, this is no longer the case.

The right to asylum stems from the 1951 Refugee Convention and the subsequent 1967 Refugee Protocol, one or both of which has been ratified by 148 State parties. The United States has only ratified the 1967 Refugee Protocol. Nevertheless, this is inconsequential because Article 1 of the Refugee Protocol clarifies that, “the States Parties to the present Protocol undertake to apply articles 2 to 34 inclusive of the Convention to refugees as hereinafter defined.” Therefore, as understood by the U.S. government at the time, the United States must comply with the provisions in both the Refugee Convention and Protocol.

The Refugee Convention, in Article 33, introduces the principle of non-refoulement, which states that no State party may expel or return (“refoule”) a refugee to a country where their life or freedom is threatened on account of their “race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.” The United States incorporated this principle into its domestic law with the Refugee Act of 1980, which harmonized domestic law for asylum with international humanitarian obligations, including Article 33. The Refugee Act of 1980 allowed noncitizens to apply for asylum in the United States either affirmatively outside of removal proceedings or defensively once in removal proceedings by CBP. It also created the additional forms of humanitarian relief of withholding of removal and relief under the Convention Against Torture (CAT) as further safeguards. Oftentimes, non-citizens seek relief under CAT as well as asylum if they fear being tortured upon being returned to their home country.

Consequences of Capio

Title 42 Section 265 expulsions that take place according to Operation Capio instead of Title 8 present a plethora of concerns for international law. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the implementing body of the 1967 Refugee Protocol and 1951 Convention, explicitly cautioned States against violating the principle of non-refoulement during the COVID-19 pandemic. While the UNHCR urged States to ensure that proper public health measures are in place to quarantine individuals arriving at borders or ports of entry, it made clear that States are precluded from violating international law in taking such measures.

The Operation Capio memo contains no guidance whatsoever regarding the right of noncitizens to seek asylum based on persecution. In fact, the only form of humanitarian relief considered in the memo is based in the Convention Against Torture. According to Operation Capio, “aliens that make an affirmative, spontaneous and reasonably believable claim that they fear being tortured in the country they are being sent back to, will be taken to the designated station and referred to USCIS [United States Citizenship and Immigration Services]. Agents should seek Supervisory Guidance [emphasis added].” Not only does this statement ignore persecution aside from torture entirely, but it also requires that the claim be affirmative, spontaneous, and reasonably believable, subject to the discretion of the CBP officer and potentially USCIS.

As argued by international human rights organizations, immigration advocates, and former Senior Legal Advisor to the Department of State Harold Koh, Operation Capio plainly violates non-refoulement. It is no longer possible for non-citizens in Title 42 proceedings to receive asylum, as border protection officers only screen for a fear of torture, and thus, those non-citizens will be sent back to countries where they may endure persecution. If encountered at the border, Operation Capio dictates that they be sent back to Canada or Mexico, and if encountered at a port of entry, they will likely be sent back to their home countries without any ability to make a claim. As such, the U.S. government has used the veil of public safety and an unused quarantine-related statute to ignore the principle of non-refoulement and subvert domestic immigration law.

Recent Developments for Title 42

While the Biden Administration has rolled back several restrictive Trump-era immigration policies, Title 42 expulsions remain in effect to this day, with some slight modifications. Earlier in March 2022, the Biden administration declared that unaccompanied minors are now exempt from expulsion under Title 42 Section 265. While this change represents a minor fix, the U.S. government has not indicated any intention to stop public health expulsions altogether. Of the over 1.7 million non-citizens expelled from the United States under Title 42, over 1.2 million of these expulsions have taken place during the Biden Administration.

The U.S. domestic court system represented another avenue to invalidate U.S. violations of non-refoulement until recently. In the case Huisha-Huisha v. Mayorkas, a Washington D.C. District Court Judge granted a preliminary injunction to protect “all noncitizens who (1) are or will be in the United States; (2) come to the United States as a family unit composed of at least one child under 18 years old and that child’s parent or legal guardian; and (3) are or will be subjected to the Title 42 Process” against expulsions under Title 42 Section 265. The Judge did so purely on the basis of domestic law. The Court agreed with the noncitizens’ claims that “[n]othing in [Section] 265, or Title 42 more generally, purports to authorize any deportations, much less deportations in violation of’ statutory procedures and humanitarian protections, including the right to seek asylum.”

However, any potential relief that Huisha-Huisha v. Mayorkas may have provided was short-lived. The U.S. government appealed the decision to the Fourth Circuit. In March of 2022, the Court of Appeals decided that the executive branch may still expel noncitizens pursuant to Title 42, as long as they are not sent to places where they may be persecuted or tortured. This seems paradoxical, as Operation Capio does not grant CBP officers the authority to screen for persecution aside from torture.

Conclusion

As long as Operation Capio remains in effect, noncitizens at U.S. borders and ports of entry will not have any meaningful opportunity to raise an asylum claim. The memo does not grant noncitizens the opportunity to contest their expulsion pursuant to either the U.S. immigration code or the Refugee Convention and Protocol. To this day, the United States continues to violate the principle of non-refoulement domestically and internationally.

Nevertheless, it appears that this harmful practice may not remain for much longer. In fact, the Biden Administration has finally provided a light on the horizon by promising to end Title 42 expulsions on May 23, 2022. This may prove to be more difficult than it seems, however, as Southern Attorney Generals have already promised to fight against the rollback of Title 42 Section 265.

While it may be too late for over 1.7 million noncitizens, it is still possible for the Biden Administration, the CDC, and CBP to prevent further harm to vulnerable populations at the border. Human rights organizations, immigrant rights advocates, and the international community at-large have the ability to pressure the current U.S. Administration to administer guidance on the extinction of Title 42 expulsions and to dispute those who would keep it in place. So far, they have already been successful in forcing an exemption for unaccompanied minors. It remains to be seen whether that pressure will be sufficient to stop this illicit policy once and for all.

Author Biography: Mark Rook is a moderator for the International Law and Policy Brief (ILPB) and second year law student at The George Washington University Law School. He graduated in 2020 from the University of Pennsylvania with a degree in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics. He is also an Associate with GW’s International Law in Domestic Courts journal. His primary fields of interest are international human rights law and immigration law.