Introduction

On Monday March 28th, the Supreme Court issued an order denying certiorari in Transpacific Steel v. United States (“Transpacific”), a case appealed from the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit about the President’s statutory authority to modify import taxes (tariffs) imposed under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act to protect national security. The case arises out of President Trump’s doubling of Section 232 tariffs on Turkish steel imports in 2017 from twenty-five percent to fifty percent after the end of the statutorily prescribed timeframe.

The Supreme Court’s order denying certiorari allows the Federal Circuit’s decision to stand. This decision permits the President to modify Section 232 tariffs without a new factual determination if the underlying logic has not changed and the original proclamation of tariffs described the possible need for ongoing action.

The implications of this decision are important for the United States and the world. Although Section 232 tariffs may have lifted domestic production of targeted goods, they also raised prices for American consumers, increased costs for domestic manufacturers, depressed U.S. economic growth, and reduced global GDP. As both the Biden and Trump administrations have shown, Section 232 tariffs are also a powerful negotiating tool in U.S. foreign relations.

The Constitution grants Congress the power to implement taxes and regulate Commerce with foreign governments. Congress delegated some of that authority to the President, subject to certain time restraints. In 1976, the Supreme Court upheld this delegation in FEA v. Algonquin SNG, Inc., in part because of Section 232’s “clear preconditions to Presidential action.” Transpacific loosens Section 232’s clear time constraints and provides no meaningful check on the President’s tariff modification authority. Without a narrow interpretation of Section 232’s delegation of Congress’s enumerated constitutional tariff authority, the Federal Circuit’s decision threatens to upend the separation of powers in international trade authority.

Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act

Transpacific involves Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act, as amended in 1988 and codified as 19 U.S.C. § 1862. (The terms “Section 232” and “§ 1862” are used here interchangeably.) In that statute, Congress delegated to the President the power to restrict imports of certain goods, called “articles” in trade law, if the President concurs with a requisite finding by the Secretary of Commerce that the current level of importation of that good threatens or impairs national security. Goods targeted by Section 232 tariffs generally include scarce resources and technology such as oil, uranium, or semiconductor components.

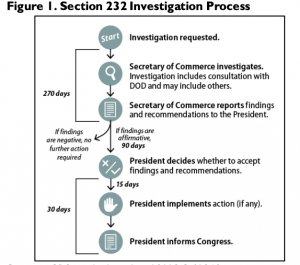

| Section 232 authority was rarely invoked after its passage during the Cold War. Following the World Trade Organization’s creation in 1995, no administration levied national security tariffs until the Trump Administration upended this trend in 2017. Since then, eight Section 232 investigations have been initiated. While the Biden Administration has reversed certain aspects of U.S. trade policy—notably expressing support for the WTO—it has maintained the Trump Administration’s use of national security tariffs to elicit concessions from trading partners. | Figure 1: Section 232 Investigation Process

Source: CRS graphic based on 19 U.S.C. § 1862 |

Congress’s delegation of power to the President through the Trade Expansion Act encompasses a multitude of trade policy tools. But following a 1988 amendment, the delegated powers were bound by a strict timeline. As amended, 19 U.S.C. § 1862(c) authorizes the President to adjust imports by deciding whether to impose tariffs “within 90 days after receiving a report [from] the Secretary [of Commerce] find[ing] that an article is being imported into the United States in such quantities or under such circumstances as to threaten to impair the national security.” If so, “the President shall . . . determine the nature and duration of the action that, in the judgment of the President, must be taken to adjust the imports . . . so that such imports will not threaten to impair the national security. . . . The President shall implement that action within 15 days.”

FEA v. Algonquin SNG, Inc.

The Supreme Court considered Presidential authority under Section 232 once before. In FEA v. Algonquin SNG, Inc., the Court decided whether Section 232(b) authorized the President to adjust imports of petroleum by imposing licensing fees, as opposed to implementing a quota. In answering that statutory question, the Court first analyzed whether Section 232 was an unconstitutional delegation of congressional authority using the “intelligible principle” test established in J.W. Hampton, Jr., & Co. v. United States. Under the J.W. Hampton test, a statutory delegation of congressional authority to the President is constitutional so long as the the statute provides “an intelligible principle to which the President is directed to conform.” The Algonquin Court held that Section 232 “easily fulfills” the J.W. Hampton test because the standards “[Section] 232(b) . . . provides the President in its implementation are clearly sufficient to meet any delegation doctrine attack.”

Decision by the United States Court of International Trade

In a unanimous three-judge panel decision, the United States Court of International Trade (“CIT”) held in Transpacific Steel v. United States that the President violated § 1862. The CIT—a federal district court with subject matter jurisdiction over international trade cases—ruled that by modifying Section 232 tariffs after the ninety day statutorily defined timeframe, President Trump exceeded the authority granted to the President by Section 232.

The CIT gave great weight to a 1988 amendment of Section 232, finding, “the temporal restrictions on the President’s power to take action pursuant to a report and recommendation by the Secretary is not a mere directory guideline, but a restriction that requires strict adherence.” The opinion continued, “there is nothing in the statute to support the continuing authority to modify Proclamations outside of the stated time-lines.”

In its reading of Section 232, the CIT cited Algonquin as Supreme Court precedent requiring the CIT to interpret the statute narrowly. The CIT opinion asserted that in Algonquin, the Supreme Court “stressed the importance of the procedural safeguards in holding that Section 232 was not an impermissible delegation of congressional authority over imports. . . . [I]f the president could act beyond the prescribed time limits, the investigative and consultative provisions would become mere formalities detached from Presidential action.” The CIT reasoned that without strict adherence to the statute’s deadlines for presidential action, Section 232 would be without an “intelligible principle” and therefore an unconstitutional delegation of Congressional authority. To avoid this result, the CIT held that the President’s tariff modification may only take place within the strict timeline defined in Section 232.

Reversal by the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit

In Transpacific Steel v. United States, the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”) rejected the CIT’s interpretation of the President’s authority under Section 232. It held that the President did not violate § 1862 because he “did not depart from the Secretary’s finding of a national-security threat; . . . [he] adhered to the Secretary’s underlying finding * * * in a short period after the Secretary’s finding and after the initial presidential action.”

Unlike the CIT, the CAFC did not define “action” narrowly. Relying on a textualist interpretation of “action” and “take action,” the CAFC said “[t]he terms . . . can readily be used to refer to a process or launch of a series of steps over time.” The opinion continued, “[President Trump’s] initial . . . action . . . itself announced a continuing course of action that could include adjustments as time passed.” Under these circumstances, the court reasoned, the President need not seek a new determination by the Secretary of Commerce finding that increased tariffs are warranted as long as the underlying rationale for the tariff increase remained the same as for the original imposition of tariffs.

The CAFC determined that Section 232 provided a statutory basis for the President’s actions. “[The] President in exercising his statutory authority to act to alleviate threats to national security from imports could announce continuing course of action within statutory time period and then modify initial implementing steps in line with announced plan of action by adding impositions on imports to achieve stated implementation objective.” (Emphasis added).

The opinion alluded to an alternative statutory path in which to read President Trump’s actions. Footnote 8 provides, “[i]f the President decides to negotiate, [19 U.S.C. 1862(c)(3)] requires a different timeline. If no agreement is entered into before the date that is 180 days after the date on which the President made his § 1862(c)(1)(A) determination to take action, or if the negotiated agreement is not carried out or effective in eliminating the threat, the President ‘shall take such other actions as the President deems necessary to adjust the imports{.}’” However, it continued on, clarifying that “[t]his appeal does not directly involve the negotiations alternative.”

Judge Reyna dissented on constitutional and statutory grounds, framing the majority’s decision as “legislating from the bench” and even “amending the Constitution” to grant the President “unchecked authority over the Tariff.” Judge Reyna argued that because Article I Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution grants the power to “lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts, and Excises” and “regulate Commerce with foreign Nations,” and because Section 232 is a trade statute, its delegation of congressional power to the President should be interpreted narrowly. Quoting King v. Burwell’s rationale that “the words of a statute must be read in their context and with a view to their place in the overall statutory scheme[,]” the dissent argues that Section 232’s plain meaning and context “demonstrate that the President must act within the specified time limits or else forfeit the right to do so until the Secretary of Commerce provides a new report.” It contended, “[t]he majority’s malleable interpretation of § 232 opens the door to modifications of prior presidential actions absent the Secretary of Commerce’s provision of current information.” Judge Reyna would have affirmed the CIT’s decision.

Although the Federal Circuit was careful to stipulate its decision did “not address other circumstances that would present other issues about presidential authority to adjust initially taken actions without securing a new report with a new threat finding from the Secretary,” the CIT has cited Transpacific to stay two of its previous decisions on Section 232 tariffs: Oman Fasteners v. United States and Primesource Building Products, Inc.

Transpacific’s Effect on the President’s Section 232 Actions

The Transpacific decision reads President Trump’s actions into the statutory bounds of Section 232’s presidential authority. Without strict adherence to § 1862(c)(1)(A)’s time restrictions on the Executive’s delegated power to increase tariffs, the President may, for an undefined period of time, increase tariffs that were originally implemented within Section 232’s defined timeline. The only limiting factor is that the original proclamation must include language describing an ongoing course of action or a future action that is intended to achieve the same goal. Transpacific leaves open the possibility of challenges in individual cases based on the “staleness” of the President’s actions.

Transpacific exacerbates a procedural imbalance between the statutory requirements for reducing tariffs versus those required to implement new tariffs or raise existing ones. 19 U.S.C. § 1862(a) prohibits the President from “decreas[ing] or eliminat[ing] the duty or other import restrictions on any article if the President determines that such reduction or elimination would threaten to impair the national security.” In other words, before reducing tariffs, the President must determine that doing so will not harm national security. Even if the President decides not to take any action upon a finding that tariffs have not achieved their goal of alleviating a threat to national security, the President “shall publish in the Federal Register such determination and the reasons on which such determination is based.” Following the CAFC’s Transpacific decision, no such reasoned publication is required for a President to increase tariffs already implemented, even if the modification occurs after the conclusion of the statutory timeframe. This imbalance in procedural requirements creates a “ratchet-up” effect, whereby Section 232 tariffs are easier to increase than to decrease.

Conclusion

Section 232 is a statutory delegation of Congress’s constitutionally granted power to impose tariffs and regulate international trade. Its 1988 amendment provided time limits to which the President’s actions must conform. Transpacific Steel v. United States authorizes the President to engage in ongoing action under Section 232 and extends that authority after the termination of § 1862(c)’s 90-day limit. So long as the President’s initial “action” announced ongoing or future actions, the President may modify tariffs indefinitely until he is satisfied that they have achieved their goals—a day that may never come.

Author Biography: Eric Cunningham is a 2023 J.D. candidate at The George Washington University Law School, Senior Executive Editor of The George Washington Law Review, Research Assistant to Professor Caprice L. Roberts, Vice President of the International Law Society, and Moderator of the International Law and Policy Brief. Eric received a B.S. in economics from West Virginia University. He previously held accounting roles in the software industry and served on the board of TransitMatters, a nonprofit advocacy group.