Debates about the future of healthcare within the United States have carried on for decades. With no clear solution for skyrocketing costs, and a substantial percentage of the population left completely uninsured, the massive costs associated with certain treatments leave many with insurmountable debt. Others turn to attempts to crowdfund their healthcare, using sites like GoFundMe as a last resort for help. Despite the adamantly opposed positions held by both sides, one thing is clear to everyone: something is clearly broken, and the system as it is causing immense preventable suffering. When looking for answers to systemic problems, especially ones as universal as the medical treatment of your population, it can be useful to examine the solutions that other similarly developed nations have turned to to solve the exact same dilemma. By evaluating the healthcare outcomes of these nations in comparison to the United States, hopefully something important can be begun. A conversation on what kind of healthcare system actually works.

When debating the topic of healthcare, oftentimes some Americans will claim that, despite the costs, our system is one of the best in the world at actually treating disease. While the United States does invent most of the new medicines globally, and the innovation caused by the potential for large revenue has debatable benefits, the idea that our system is superior because of it can be tested by a comparison of healthcare outcomes.

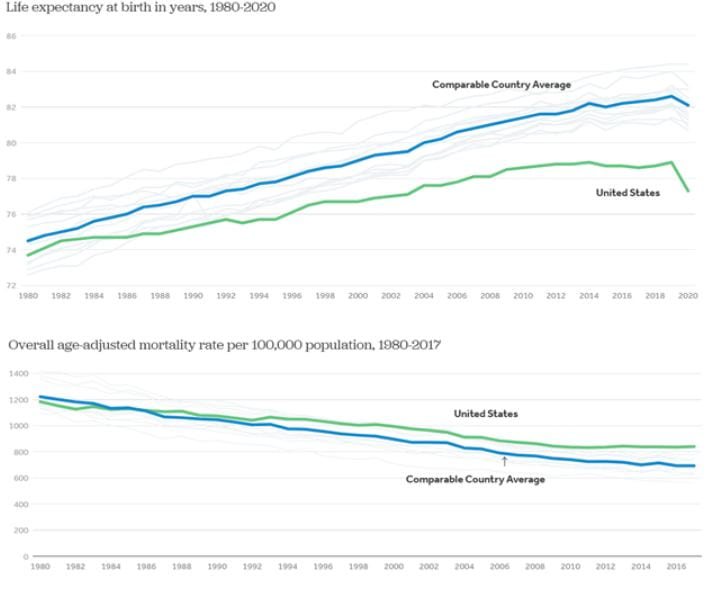

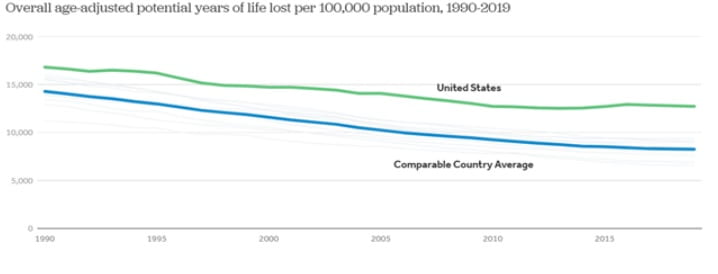

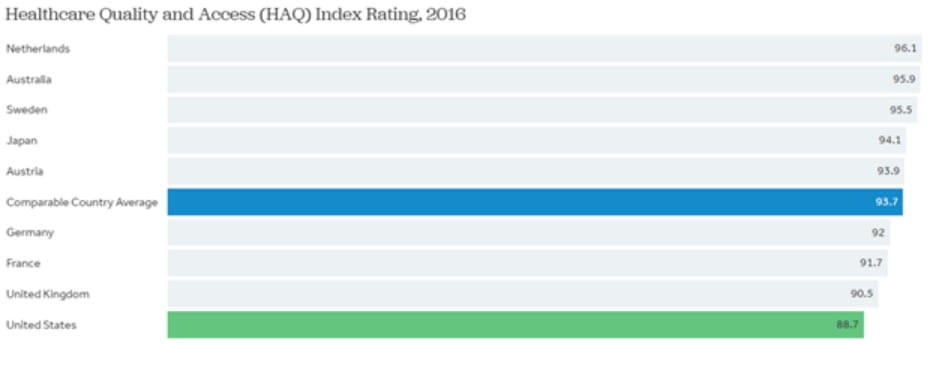

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation Analysis of OECD data

These charts do not tell the entire story, and the same article they are found in goes on to describe other strengths and weaknesses of the systems, like the 30-day mortality rate following heart attack and stroke, where the United States performs the best overall among all the countries measured. These broad categorical overall statistics could be a product of other factors, like the higher prevalence of obesity or other conditions linked with increased mortality (in comparison to these nations). However, “the U.S. ranks last in a measure of health care access and quality, indicating higher rates of amenable mortality than peer countries.”

All this is to say: at least some of the increased mortality the United States experiences, in comparison to its peers, could be avoided by greater access to quality health care. An expected response to the statistics quoted above could be that these outcomes consider people with less resources who inherently have less health care access in the American system. Surely wealthy Americans’s outcomes must be significantly better than those of comparable countries with universally accessible systems. However, that does not appear to be the case. A study conducted in 2020 found that although the privileged within the United States do better than average Americans, they did not do significantly better than the average person in comparable countries with universal access.

It is easy enough to poke holes in any system or policy. No matter what structure or solution is proposed there is usually some demographic harmed by it. If we negotiate drug prices as a nation, like many others do, won’t that harm the healthcare industry’s willingness to innovate? Won’t that harm the careers and livelihoods of all of the people employed by these companies, hospitals, and organizations? It is true that some occupations, like health care workers, elicit more sympathy than the stereotypical pharmaceutical executive. But it could be argued that the financial incentives that lead to the creation of new pharmaceutical products are more important to the healthcare outcomes of individuals than the actions of any individual healthcare practitioner. Regardless, every side of this debate recognizes the need for change and looking at which countries have achieved some success allows us to start a conversation backed up by hard numbers instead of hypotheses.

When it is found that even among the richest Americans the outcomes are not significantly better than the average citizen of other comparable countries with greater accessibility, we should all stop and ask what exactly are we risking bankruptcy for? The optimistic hope that we will not be it? The costs to individuals, and the system as a whole, do not justify the outcomes seen throughout the country. The fear of an increased bureaucracy does not seem to acknowledge that the United States already spends four times more per person on hospital administration. When the United States routinely falls short of other developed nations in almost every category the conversation should begin on what those countries are doing right instead of continuing to assert the success of a system that continually destroys the lives of individuals.

Author Biography: Connor Noel is a moderator for the International Law and Policy Brief (ILPB) and J.D. candidate at The George Washington University Law School. He Received a B.S. in Cellular and Molecular Biology at Christopher Newport University.