Changing Demographic Trends in South Korea

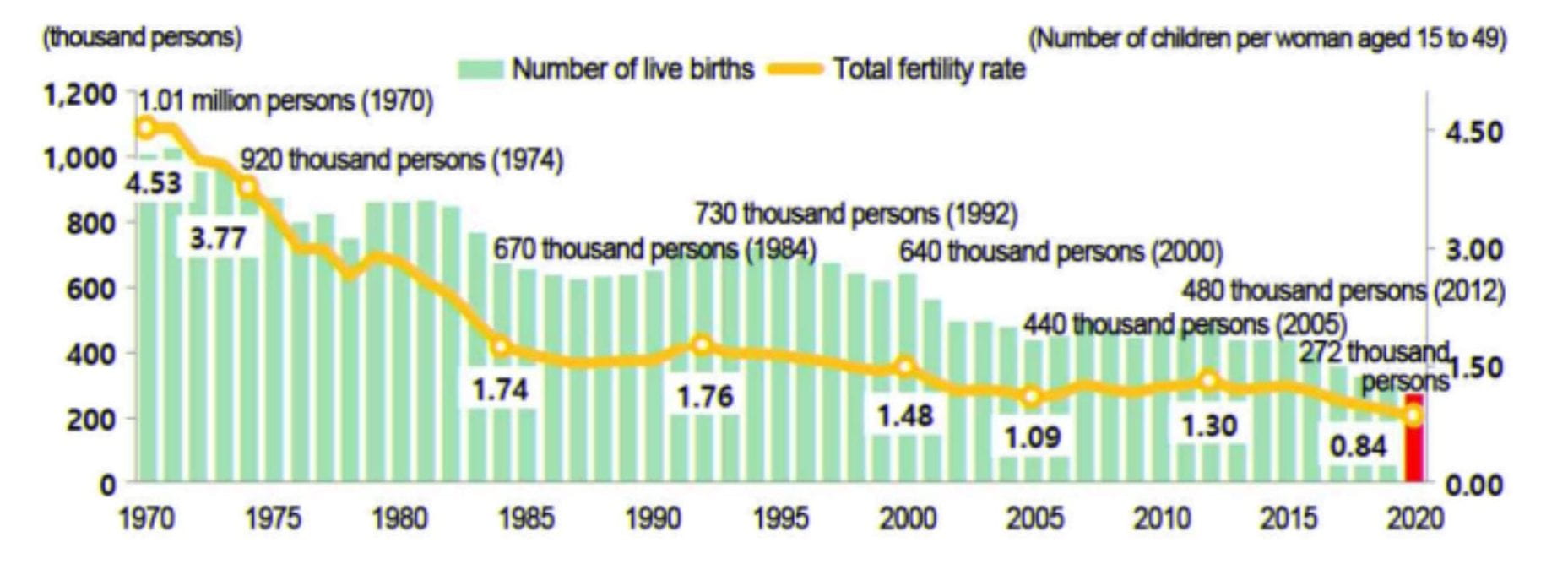

Over the past sixty years, South Korea has experienced remarkable growth in key development indicators like life expectancy, gross domestic product (GDP), GDP per capita, and literacy. Entering the third decade of this century, however, one key statistic is startlingly low; at 0.84, South Korea’s birth rate is the lowest of any country in the world. Causes of this phenomenon are multifarious and complex, but it is clear that the population of the country is aging with no near-term prospect of rebounding. It is projected to become a “super-aged society” by 2025. If Korea is to continue its notable economic development and maintain its current level of government expenditure, it will need to look beyond its borders.

Source: Statistics Korea

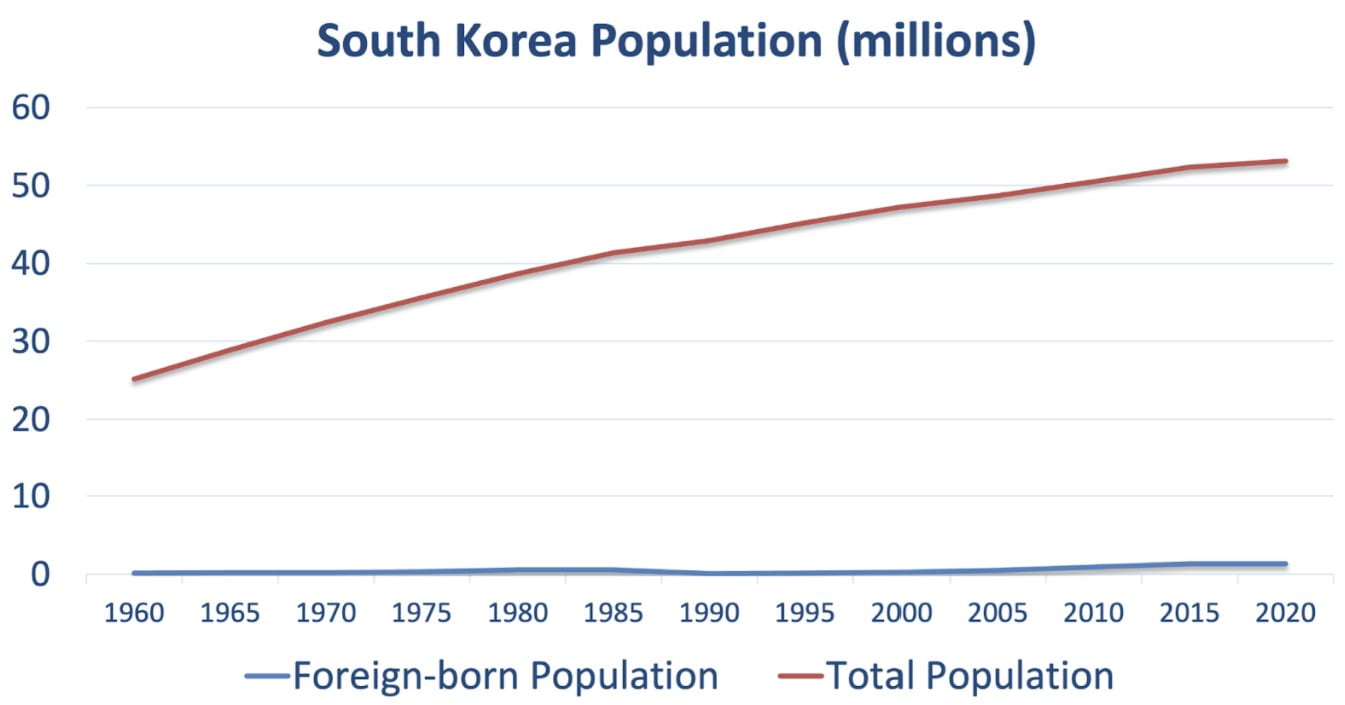

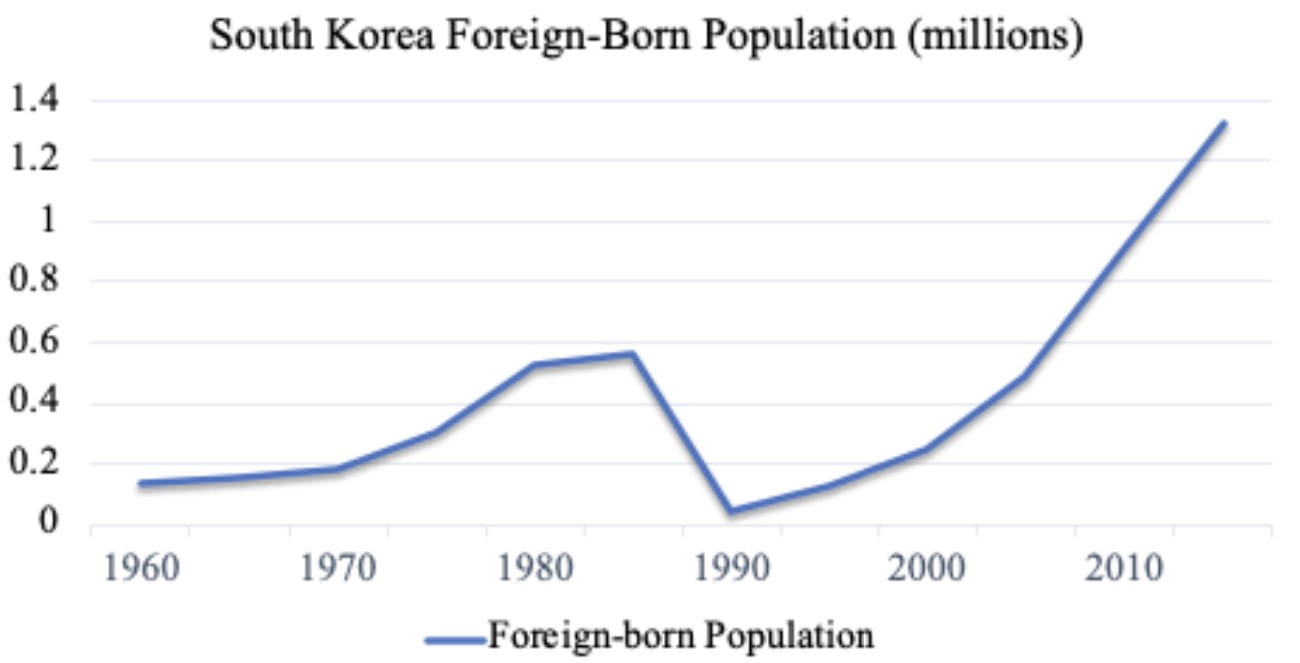

There are 1.35 million foreign-born individuals in South Korea, accounting for approximately 2.6% of the country’s population of 51.78 million. That is the highest proportion of foreigners at any time in the country’s history, and a twenty-five fold increase from 1990. Even so, South Korea is still one of the most ethnically homogenous developed countries in Asia. The nearest analog is the 1.7% foreign-born population in Japan, which is similarly experiencing record-low birth rates and a declining population. Other developed Asian polities like Hong Kong (38.9%), Singapore (45.4%), and Macao (58.3%) are significantly more cosmopolitan.

Source data: The World Bank

North Korean Defectors

South Korean immigration policy has traditionally focused on ethnic Koreans fleeing North Korea, mirroring the population’s preference for co-ethnic migrants to those of other ethnicities. This policy is more accurately described as a migration policy in the Korean context since the Republic of Korea (South Korea) does not recognize the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea)’s claim to territory on the Korean Peninsula. South Korea therefore considers all North Koreans—with rare exceptions—to be formal citizens of South Korea. Even so, there is some evidence that South Koreans are less willing to welcome and assimilate North Koreans than in the past. Nevertheless, most southerners continue to support acceptance of northern defectors.

Non-Korean Refugees

Views of non-Korean refugees—particularly Muslims—are much more negative than perceptions of ethnic Koreans. This was particularly evident in 2018, when about five hundred Yemenis entered Jeju Island, a vacation destination off the southern coast of the Korean peninsula, to seek asylum. To bolster the island’s tourism industry, the Korean government allows visitors from more than one hundred countries to visit Jeju without a visa. This permissive policy allowed the Yemenis to enter South Korean territory to seek refuge from the ongoing conflict in their home country, which the United Nations calls “the largest humanitarian crisis in the world.”

Many Koreans decried the Yemenis’ arrival as a gateway to radical terrorism within South Korea and demanded that they be returned to their home country. Some Koreans accused the asylum seekers of being “fake refugees.” An online petition accumulated over 714,000 signatures asking President Moon Jae In to stop accepting refugees, particularly those from Yemen, and reform the country’s refugee system. In response, the South Korean government removed Yemen from the list of countries whose nationals do not require a visa to enter. In the end, only two of the Yemenis were granted refugee status. The low acceptance of the Yemeni migrants is indicative of South Korea’s treatment of refugee applicants generally. “Of 40,400 non-Koreans who have applied for refugee status in the country since 1994, only about 840, or about 2 percent, have received it.”

While many Koreans harbor animus toward foreign refugees, the fervent discourse over the Yemeni migrants in Jeju seems unique. In 2015, the Korean government “granted humanitarian stay permits or refugee status to over 600 Syrians” with “little to no society-wide controversy.” Following the recent collapse of the U.S.-backed government in Afghanistan, President Moon announced that Afghans who worked for the South Korean government would be welcomed as “persons of special merit.” This novel legal status was conferred to the Afghans to avoid anti-refugee harassment similar to that experienced by the Yemenis in Jeju. The Afghan evacuees were flown from Pakistan to Incheon Airport and included “medical professionals, vocational trainers, IT experts and interpreters who worked for Korea’s embassy and its humanitarian and relief facilities in Afghanistan, as well as their family members.” President Moon highlighted the moral virtue of welcoming the Afghans to Korea. This scenario offers a template that should be followed when communicating about foreign refugees to Korean audiences in the future.

While the low acceptance rate of refugees to South Korea is undoubtedly attributable to negative perception, it may equally be caused by an acute lack of state capacity to process applications. In 2018, “only thirty-nine government officials [took] part in the refugee status determination process, and among them only twenty-eight processed the first level assessment.” If the country wished to accept more migrants, it would surely need to recruit more officials.

Takeaway

South Korea’s population is aging rapidly. With record-low birth rates, the country will need to encourage immigration or face the prospect of a shrinking economy and an inability to financially or materially support its elders. Despite nativism and a lack of governmental support, the international refugee population in South Korea has increased from just five in 2000 to 3,498 in 2020. Still, it is one of the lowest of any comparable nation.

South Korea should welcome refugees, not only because it is humane to do so, but also because refugees will help bolster the country’s population and support its continued economic growth. Increasing access to visas for foreign migrants and expanding state capacity to process asylum applications will go far toward achieving this goal. Ultimately, Korean acceptance of immigrants and its ability to reverse its declining population will require a shift in societal views toward ethnic minorities—a change that can only be made by the citizens themselves.

Author Biography: Eric Cunningham is a 2023 J.D. candidate at The George Washington University Law School, vice president of the International Law Society, member of The George Washington Law Review, and moderator of the International Law and Policy Brief. He received a B.S. in economics from West Virginia University. Prior to studying at GW Law, Eric held accounting roles in the software industry and served on the board of TransitMatters, a nonprofit advocacy group dedicated to improving public transportation in Greater Boston.