On June 30, 2020, the People’s Republic of China inserted strict new national security provisions into Hong Kong’s Basic Law. The amendments grant broad authority to security officials in the semi-autonomous region and outlaw many forms of speech and assembly. Over a year after the National Security Law’s (NSL) passage, there is consensus among human rights organizations that the NSL has gravely injured freedom and rule of law in Hong Kong. Beijing’s enactment of the NSL followed years of social unrest and popular protests. Recent demonstrations include those in 2012 over proposed nationalist education reforms, the 2014 pro-democracy Umbrella Movement, and the 2019-2020 Anti-Extradition Law Movement.

Thirteen months after the NSL’s enactment, the first conviction under the law was handed down to Tong Ying-kit, who held a flag bearing the phrase “Liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our times” while driving his motorcycle into a group of police officers. A specially-appointed three-judge panel sentenced Tong to nine years in prison for “sedition” and “terrorism,” reasoning that Tong’s actions were “capable of inciting others to commit secession” and his flag was “at the very least capable of having [a secessionist] meaning.” The judges seemed to specifically criminalize the phrase “Liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our times” in their decision. This broad application of the NSL to speech that is capable of having secessionist meanings bodes poorly for over one hundred people who were arrested under the law since 2020.

Violations of the Sino-British Handover Agreement and Hong Kong Basic Law

The National Security Law contradicts provisions of the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration, which transferred governance of Hong Kong from the United Kingdom to China in 1997. The handover agreement purportedly guarantees that Hong Kong’s people would continue to enjoy freedom of “speech, of the press, of assembly, of association, [and] academic research.” However, the National Security Law established vague new criminal offenses, including “secession, subversion, organization…of terrorist activities, and collusion with a foreign country…to endanger national security” which are defined broadly and enforced selectively. This is a formula for oppression.

Democratic Systems Dismantled

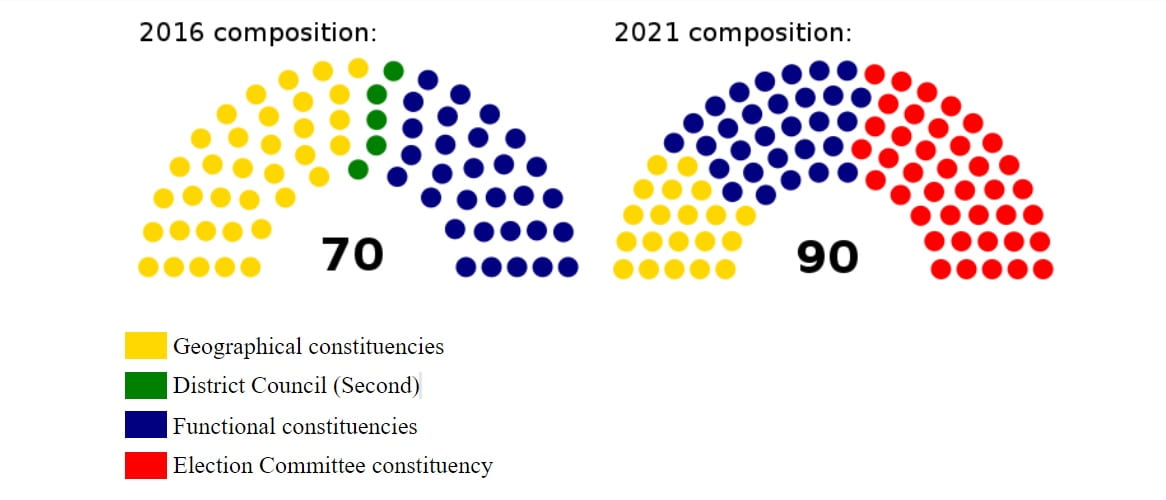

The Beijing government has used the National Security law as part of a wider effort to undermine democracy in Hong Kong. In November 2020, the NSL was invoked to disqualify four “unpatriotic” pro-democracy legislators from the region’s Legislative Council, or “LegCo,” a semi-representative legislative body. The remaining fifteen pro-democracy lawmakers resigned in solidarity, calling the disqualifications a “death-knell for Hong Kong’s democracy fight.” On July 13, 2020, the Hong Kong government announced that LegCo elections would be postponed for one year, citing the COVID-19 pandemic. The government again postponed the election to December 19, 2021 and altered the fundamental structure of the body to ensure “patriots” govern Hong Kong. The new “Improving Electoral System (Consolidated Amendments) Ordinance 2021” reduces the number of seats elected directly by “geographic constituencies” from thirty-five to thirty, and adds forty seats elected by a Beijing-influenced Election Committee. Lo Kin-Hei, chairman of Hong Kong’s Democratic Party, said the electoral changes were “the biggest regression of the system since the handover.” Hong Kong’s Chief Executive Carrie Lam and major pro-Beijing organizations supported the changes.

Source: FumiHayashi, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Freedoms Eroded

Press freedoms in Hong Kong have deteriorated markedly in the past year. In June 2021, Hong Kong authorities arrested Jimmy Lai, owner of Apple Daily News and outspoken critic of the Chinese central government, and sentenced him to twenty months in jail for his participation in 2019 pro-democracy protests. He faces two other charges under the NSL, carrying a maximum of a life sentence. Nine other prominent activists were sentenced on the same day. Police raided the offices of Apple Daily and ordered the paper to cease operations, claiming it “colluded with foreign forces.” The paper announced its closure shortly thereafter “in view of staff members’ safety.” Choy Yuk-ling, a journalist and producer of a documentary focused on Hong Kong police’s collusion with triad gangs during the Yuen Long Incident, was convicted and fined for her reporting.

Academics and students have not escaped similar fates. On July 28, 2020, The University of Hong Kong (HKU) fired pro-democracy activist Benny Tai from his tenured position as a professor of law. Eight students were arrested on December 7, 2020 for participating in a peaceful protest at the Chinese University of Hong Kong the prior month. Three of those were charged under the security law with “inciting secession.” Professors at the Chinese University of Hong Kong were pressured to resign and turn themselves in to the police after being accused of participating in and supporting protests. These events are a startling departure from Hong Kong’s long-standing respect for academic freedom and are only a few examples of the alarming degradation of academic independence in the region. The law also chills the exercise of free speech and academic freedoms by scholars outside of Hong Kong who might be at risk if they were to enter Hong Kong or mainland China.

Response by Hong Kong Residents and the International Community

Many Hong Kongers have decided to leave the region. Observers estimate that hundreds of thousands have emigrated from Hong Kong since June 2020, mostly to the United Kingdom. The Hong Kong government reacted by passing a new immigration law granting immigration authorities the power to prevent people, without a court order, from entering or leaving the city. This law further violates the Sino-British Joint Declaration’s protection of free movement and mirrors “exit bans” that are often used against dissidents in mainland China. Residents who stay are becoming less confident in Hong Kong’s democracy, rule of law, and stability.

Western powers have resisted the anti-democratic tide in Hong Kong with scathing rhetoric and significant policy enactments. Britain, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Germany, Finland, the Netherlands, and Ireland all suspended extradition agreements with Hong Kong for fear that detainees would be forwarded to mainland China’s judicial system.

In July 2020, the United States passed the Hong Kong Autonomy Act, imposing sanctions on officials and institutions in China and Hong Kong deemed to have violated the region’s autonomy. At the act’s signing ceremony, President Trump also signed Executive Order 13936 on Hong Kong Normalization, revoking Hong Kong’s special trade status and directing U.S. government agencies to eliminate policies granting preferential treatment to Hong Kong as compared to mainland China. The U.S. Department of State released a report in March 2021 accusing the Chinese Communist Party of “systematically dismantl[ing] Hong Kong’s political freedoms and autonomy,” and alleging police brutality against protesters, arbitrary arrests, bail wrongfully denied to detainees, and extratorial application of the National Security Law.

The United Kingdom, the region’s former colonial ruler, opened new immigration pathways for Hong Kong residents. Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced that holders of a British National (Overseas) passport and their dependents would be offered a fast-track to UK citizenship. An estimated 300,000 Hong Kongers are expected to apply for citizenship through this program. The policy is widely viewed as a rebuke of Beijing’s crackdown in Hong Kong.

Looking Forward

Hong Kong will remain a global financial capital in the near-term, as China still relies on its stock exchange and access to foreign investment and capital markets. However, leaders of foreign governments and multinational corporations must decide whether the status quo in Hong Kong can remain tenable in the face of the region’s rapidly deteriorating human rights. Democratic governments should act quickly to ensure Hong Kong’s freedom and protect its people from further injustice.

Author Biography: Eric Cunningham is a 2023 J.D. candidate at The George Washington University Law School, Vice President of the International Law Society, member of The George Washington Law Review, and moderator of the International Law and Policy Brief. He received a B.S. in economics from West Virginia University. Prior to studying at GW Law, Eric held accounting roles in the software industry and served on the board of TransitMatters, a nonprofit advocacy group dedicated to improving public transportation in Greater Boston.