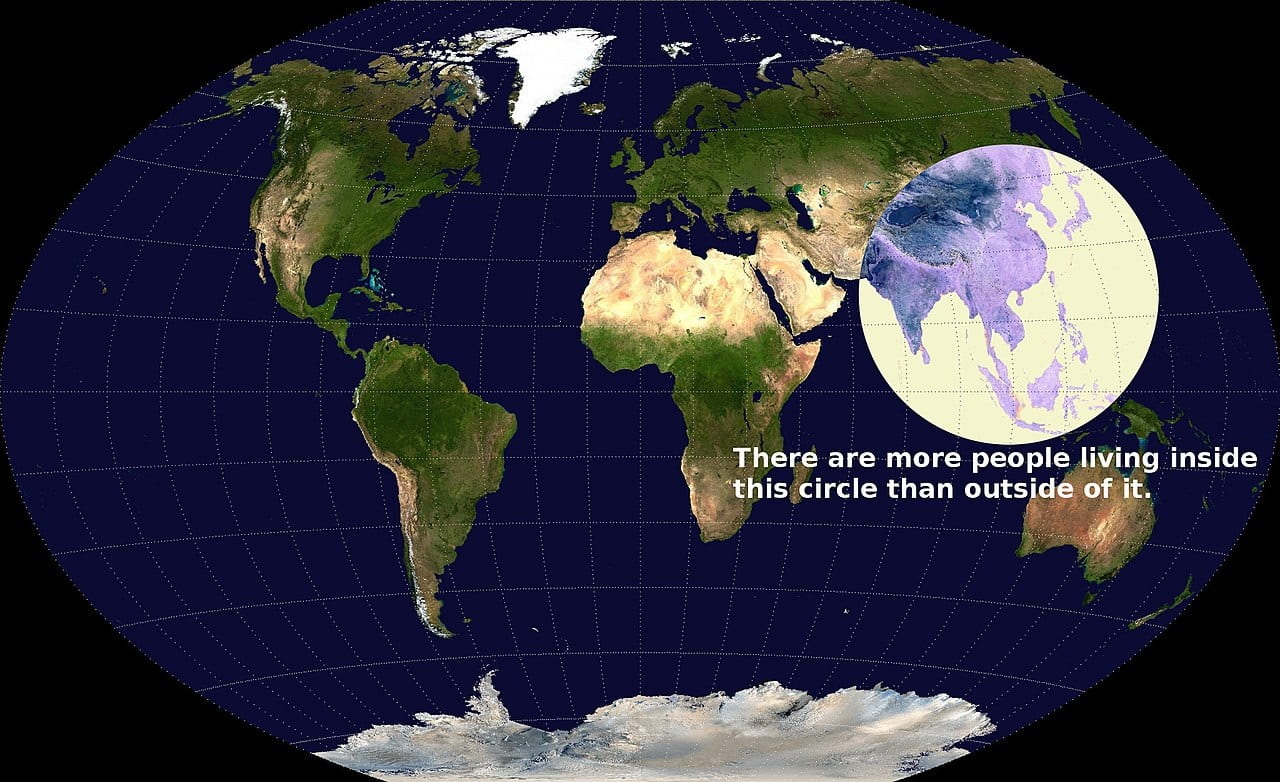

The 21st century is called the “Asian Century” and not without reason. The image below shows the Valeriepieris circle, a hypothetical circle in Asia that contains more than half of the world’s population. In other words, more people live inside the circle than outside of it.

Many of the world’s most populous—not to mention economically and militarily powerful—countries are to be found within the circle. In terms of population, they include (in terms of ranked population): (1) China, (2) India, (4) Indonesia, (5) Pakistan, (8) Bangladesh, (11) Japan, and (13) Philippines, all of which have over 100 million inhabitants. Countries with 70 million or more people include the combined population of the two Koreas, as well as (15) Vietnam, and (20) Thailand. If we include all the countries that fall within the continent of Asia, the list also contains (9) Russia, (17) Turkey, and (18) Iran.

What does this mean for students and practitioners of international and comparative law? Asia matters, both in terms of how individual countries, representing more than half of the world’s population, conceive of the law, and in their approaches to international law.

From territorial disputes in the South China Sea and the Himalayas, to domestic legal regimes’ handling of the COVID-19 crisis, to trade deals and economic models, to innovative constitutional developments, there is a lot going on in contemporary Asia, and many lessons for the rest of the world. Large countries—especially China and India—will be closely watched and emulated or rejected as models for other developing countries based on their successes or failures.

Most interestingly, the rise of Asia will likely change the trajectory of international law. After the aftermath of World War II, the United States and Europe have pursued a transatlantic, institutionalist foreign policy designed to shore up democracy and human rights. This was done in order to prevent a repeat of the horrors of nationalist militarism, total war, and genocide. This contrasts with a different foreign policy orientation, one pursued by European powers prior to World War II, as well as one that characterizes many Asian and Middle Eastern states today. This orientation focuses more on geopolitics, foreign policy realism, and “great-power competition.”

Yet, balance of power and great power politics are evident throughout Asia; witness, for example, the rivalries between Turkey and Russia, Saudi Arabia and Iran, between multiple powers in Afghanistan, India and China, and China and multiple Southeast Asian countries. As Tanner Greer, a journalist and researcher focused on contemporary security issues in the Asia-Pacific region, points out:

At the birth of the post-war consensus, Asian powers were colonies or recent conquests. They have far less invested in these transatlantic multilateral structures than Paris or Berlin. Asian elites are consequentially far less concerned with their erosion than their European counterparts. Nor are Asian publics especially enamored with Western European norms and values. European fear of nationalism has no purchase on a continent where political identity is shaped less by memories of the Western Front than by the glories of national revolt against Western imperialism. Many Asian powers, including several of America’s treaty allies, are lukewarm on liberalism.

This is not to say that most Asian countries want to overthrow the post-war, rules-based order championed by the United States. Many states in the region view such an order as a safeguard against China’s power, which many see as seeking to reconfigure geopolitics in its favor through economic and military means. Rather, they want there to be rules and trade deals between Westphalian nation-states and alliances of nation-states without committing to Western institutions and multilateralism, which they fear would subsume their hard-won, post-colonial sovereignty. International institutions such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) generally focus on economic issues, and when crises arise, such as the recent military coup in Myanmar, ASEAN generally acts as a mediator rather than as an enforcer of legal rights and sanctions. While this approach could be seen as lacking teeth, it nonetheless has certain advantages, particularly in a region prickly about sovereignty. Mediation and informal ties between leaders also affords a more flexible approach to foreign relations—including protecting human rights—than one characterized by strict legalism.

Therefore, a world increasingly dominated by Asian (and non-Western) states would approach international conflicts very differently from the European model. A Singaporean diplomat characterized an American proponent of this model as “[having] no stomach for competition, and [thinks] of foreign policy as humanitarian intervention.” A European approach to international conflicts risks over-formalization and over-institutionalization whereas an alternative approach would focus on geopolitical and strategic calculations, give-and-take, and national interests. Witness, for example, the way that this approach led to diplomatic relations between Israel and several Arab countries: Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Sudan, and Morocco all recognized Israel and established diplomatic relations with it. Of course, alternatively, there are many risks that could accompany this more nation-based approach including extreme nationalism and sabre-rattling that could inhibit pragmatism.

With the election of the U.S. President Joseph R. Biden, some may hope that international relations and law will return to a perceived golden age of transatlanticism, cooperation, and institutionalism, but this cannot be so. Attitudes toward power are changing in the United States and Europe. Additionally, geopolitical realities of Asia, home to over half of the world’s population, are pushing international relations in a very different direction. An international law dominated by Asian concerns will focus more on geopolitical issues such as territorial disputes, military matters, and trade issues, rather than multilateralism and human rights: a law of nations rather than a law of individuals. Practitioners and students of international law should therefore continue to look closely at Asia and Asian countries.

Author Biography: Akhilesh (Akhi) Pillalamarri is the Moderator-in-Chief of the International Law Society’s International Law and Policy Brief (ILPB) at The George Washington University Law School. He has a Master of Arts in International Security Studies Policy from Georgetown University, and worked as an international relations journalist before attending law school. His interests include international law, comparative law, and national security law.