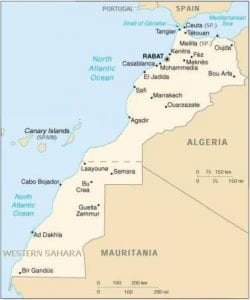

The Kingdom of Morocco has long claimed the territory to its south—the erstwhile Spanish colony of Spanish Sahara, now known as Western Sahara—in its entirety. While many countries have expressed support for Moroccan rule over Western Sahara, often in the framework of autonomy for that region, the United States recently became the first major country to recognize Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara. On the other hand, the United Nations (UN) recognizes a local group, the Polisario Front, as the representative of the people of Western Sahara. The Polisario Front-proclaimed Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) controls only about 20 percent of the territory of Western Sahara, and while it is a member of the African Union (AU), it is not a member of the Arab League.

Historical Background and ICJ Decision

Spain ruled Western Sahara from 1884 to 1975. Spain laid claim to the territory after the 1884 Berlin Conference, during which European powers carved up Africa. It legitimized its rule through treaties with the local, mostly nomadic tribes who inhabited the sparsely-inhabited areas of the western Sahara Desert that subsequently became the colony of Spanish Sahara. Nonetheless, Spanish rule over the territory remained tenuous in the face of multiple local revolts. In the early 20th century, France established a protectorate (1912-1956) in Morocco, to the north, and a colony in Mauritania, to the south.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

By 1975, Morocco and Mauritania were independent, and the Spanish were on the verge of leaving Western Sahara. Mauritania briefly claimed parts of Western Sahara, but ultimately vacated these claims, leaving the field to Morocco. Morocco claimed that there were longstanding ties between itself and the tribes of Western Sahara, which share both religion (Islam) and language (Arabic) with Morocco. (Up to 40 percent of Moroccans also speak Berber languages.) In an era before territorial borders were delineated with precision, this meant that there were some traditional ties between the tribes of the region and the sultan of Morocco. Morocco made this case as it sought to press claims to the territory by seeking an advisory opinion on the status of the region from the International Court of Justice (ICJ). The opinion, dated October 16, 1975, read:

As evidence of its display of sovereignty in Western Sahara, Morocco has invoked alleged acts of internal display of Moroccan authority and also certain international acts said to constitute recognition by other States of its sovereignty over the whole or part of the territory….The principal indications of “internal” display of authority invoked by Morocco consist of evidence alleged to show the allegiance of Saharan caids to the Sultan, including dahirs and other documents concerning the appointment of caids, the alleged imposition of Koranic and other taxes, and what were referred to as “military decisions” said to constitute acts of resistance to foreign penetration of the territory. In particular, the allegiance is claimed of the confederation of Tekna tribes, together with its allies, one part of which was stated to be established in the Noun and another part to lead a nomadic life the route of which traversed areas of Western Sahara: through Tekna caids, Morocco claims, the Sultan’s authority and influence were exercised on the nomad tribes pasturing in Western Sahara.

Morocco also argued that its various treaties with Spain, Great Britain, and the United States indicated its sovereignty over Western Sahara. However, ultimately the ICJ sided with the Spanish and Sahrawi view that alliances between the tribes and the sultan of Morocco are “in accord in not providing indications of the existence, at the relevant period, of any legal tie of territorial sovereignty between Western Sahara and the Moroccan State.” The court also went on to note that:

[T]he present territory of Western Sahara was the foundation of a Saharan people with its own well-defined character, made up of autonomous tribes, independent of any external authority; and that this people lived in a fairly well-defined area and had developed an organization and a system of life in common, on the basis of collective self-awareness and mutual solidarity. In Western Sahara, it says, a clear distinction was made by the population and in literature between their own country, the country of the nomads, and other neighbouring countries of a sedentary way of life…

However, in Morocco, the parts of the opinion that emphasized the traditional ties between the tribes of Western Sahara and the monarchy were emphasized, and in November 1975, the country staged the Green March, during which 350,000 unarmed volunteers occupied Western Sahara. A war began in 1976 with the Polisario Front—which was backed by neighboring Algeria—and ended in a UN-backed ceasefire in 1991. After the war, Morocco controlled over most of the territory, which it describes as its southern provinces. Subsequently, Morocco cemented its hold over Western Sahara through infrastructure and incentivising Moroccan settlement of the region. A UN-backed referendum on the future of Western Sahara has never occurred due to Moroccan resistance, and after several attempts for a resolution to the dispute, Morocco instead proposed a plan that would give the region autonomy under Moroccan sovereignty.

The Moroccan and Sahrawi positions thus reveal a fundamental tension between two principles, both enshrined in the United Nations Charter: self-determination (Article 1(2)) and territorial integrity (Article 2(4)).

Recent Developments

This status quo persisted for two decades. Then, on December 10, 2020, the United States recognized the sovereignty of Morocco over Western Sahara in exchange for the establishment of diplomatic relations between Israel and Morocco (Morocco claims it would open “liason offices”)—a matter completely unrelated to the Western Sahara dispute. However, the decision was in line with geopolitical trends current throughout the Middle East and North Africa: the drawing together of most Arab countries, especially Arab monarchies, and closer ties between those Arab states and Israel. The UAE, Jordan, and Bahrain recently opened consulates in Laayoune, the capital of Western Sahara, signifying their support of Morocco’s position.

The outgoing administration of President Donald J. Trump had already concluded deals that lead to the recognition of Israel by the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain, and Sudan, as well as informal ties between Israel and Oman and Saudi Arabia. From the perspective of the Trump administration, ties with Israel were much more important than the future of Western Sahara, and the Israel-Morocco deal was merely the latest diplomatic triumph.

The president of the United States—not Congress—has the constitutional power to extend or deny recognition to foreign countries. Several Supreme Court cases including United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp. (1936), Goldwater v. Carter (1979), and especially Zivotofsky v. Kerry (2015) have held that the “President has the exclusive power to grant formal recognition to a foreign sovereign,” as well as the power to withhold such recognition. This also includes recognizing the territorial extent of other states, especially if there is an absence of Congressional legislation on the topic. Therefore, the onus now lies on the administration of President Joseph R. Biden, Jr. as to whether to maintain or reverse the United States’s recognition of Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara.

Geopolitical Realities

Despite the strange entanglement of the Western Sahara and Israel issues and the advisory opinion of the ICJ, the United States should continue to recognize Morocco’s sovereignty over Western Sahara because this aligns with geopolitical realities, and is the best way forward for the people of the territory, who would be exchanging a limbolike status for autonomy and a voice in the political structure of Morocco; in fact, there is already significant political participation in the part of Western Sahara integrated into Morocco. This is a better outcome for the people of the region than the perpetual marginalization in refugee camps that characterizes life in Polisario Front controlled territory. That the Biden administration did not walk back the U.S. recognition of Morocco provides evidence that the current president may have come to the same conclusion.

Morocco is an important middle power, on good terms with most of its Arab neighbors, the members of the European Union (EU), and the United States. The United States considers Morocco to be a major non-NATO ally. Morocco’s human rights record and democracy indicators have improved substantially over the past decade, and Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara is supported by all its major players and parties. There is therefore no strong constituency, internationally or domestically, that would expend much effort to champion Western Sahara, with the exception of Morocco’s neighbor and rival, Algeria.

The economic and political viability of an independent Western Sahara—with its small, nomadic population and sparse development—would be another question many states could have: an independent Western Morocco would be at serious risk of becoming a failed state. Even among the Sahrawi, opinions are mixed. According to John Peter Pham, a former U.S. Special Envoy for the Sahel:

The Polisario Front’s pretensions to represent all Sahrawis is belied by the fact that its base of support is among some of the Reguibat tribes of the east, while the Reguibat tribes in the western part of the territory as well as the Tekna confederation are largely pro-Moroccan. In fact, while the Polisario Front and its sympathizers are wont to romanticize the movement as a united front forged by adversity, the fact is that the attempt to create a new Sahrawi identity based on abstract principles foundered by the early 1980s and the movement internally fell back on tribal identities, rallying the Reguibat in particular.

These complexities of Western Sahara’s tribal politics are little known outside of the region, and certainly do not give much evidence for a mass drive for independence that would merit foreign support. Pham goes on to note the lukewarm attitude toward independence among many younger Saharans who have only known Moroccan administration and were educated in Moroccan universities.

The fact that the ICJ opinion was advisory and non-binding is also helpful for Morocco’s argument. Additionally, Morocco has some sympathy among other postcolonial countries, because in the context of decolonization, Morocco’s actions is perhaps not that much of an outlier—after all, China and India used similar arguments of restoring pre-colonial sovereignty to assert their claims to Hong Kong and Goa respectively. Moreover, unlike the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, Morocco did not invade and annex what was then an internationally recognized sovereign state.

Questioning Rigid International Norms

Recognizing Morocco’s control over Western Sahara could help relax overly strict norms on territoriality. In the aftermath of World War II, norms that favored a more robust legalistic approach to international problems understandably gained currency. The fixed, territorial borders of states began to be seen as sacrosanct, even when those states essentially ceased to function. Thus, while the state of Somalia existed on paper, Somaliland, which had broken away from it and actually functioned as a state, was denied international recognition because it had unilaterally seceded.

As I have previously argued, an extreme insistence on the permanence of boundaries, contrary to the political facts on the ground, leads to the perpetuation of conflict and misery. Such a stance incentivizes stubbornness—the parties involved in a dispute over territorial sovereignty or borders will hold out in the expectation that the international community will side with them, something which may or may not happen due to the political needs of individual countries. As disputes remain frozen for decades, the people of contested territories will suffer and be denied the economic and political advantages of belonging to an internationally recognized state, whether the state is a breakaway territory such as Somaliland, or a disputed region annexed by another state, such as Western Sahara. This is not an argument for states to commit acts of aggression against neighbors for the sake of acquiring territory, but an argument for the more flexible resolution of situations involving territorial sovereignty upon their arising.

Conclusion

The Western Sahara conundrum demonstrates the need to find the middle way between strict legalism and realpolitik, between the principles of territorial sovereignty and self-determination. There is no reasonable expectation that an independent Western Sahara will be a possibility anytime soon due to the scant international support for this cause and the meager firepower of the Polisario Front. Therefore, the best solution—the middle ground—is the recognition of reality: Moroccan control over the region, with the hope that the resolution of this dispute allows the people of Western Sahara greater access to political institutions, resources, and development.

Author Biography: Akhilesh (Akhi) Pillalamarri is the Moderator-in-Chief of the International Law Society’s International Law and Policy Brief (ILPB) at The George Washington University Law School. He has a Master of Arts in International Security Studies Policy from Georgetown University, and worked as an international relations journalist before attending law school. His interests include international law, comparative law, and national security law.