In a 2012 post-game interview, Washington Nationals superstar Bryce Harper, 19 at the time, responded to a question about whether he would take advantage of Canada’s lower legal drinking age with “That’s a clown question, bro.”[1] Harper sought to trademark the catch phrase for t-shirts and other merchandise[2] before ending the pursuit in 2014.[3]

In a 2012 post-game interview, Washington Nationals superstar Bryce Harper, 19 at the time, responded to a question about whether he would take advantage of Canada’s lower legal drinking age with “That’s a clown question, bro.”[1] Harper sought to trademark the catch phrase for t-shirts and other merchandise[2] before ending the pursuit in 2014.[3]

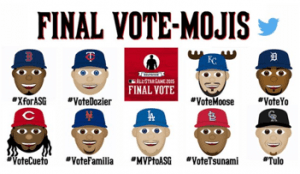

During the 2015 season, Major League Baseball and Twitter partnered to create a new method for fans to vote for the final players into its annual All-Star game. By tweeting a custom hashtag for one of the ten finalists, the tweet generated an accompanying player emoji while registering as an official vote for the player.

After nearly 25,000 tweets in the final hour of voting, Kansas City Royals third baseman Mike Moustakas (#VoteMoose) and St. Louis Cardinals starting pitcher Carlos Martinez (#VoteTsunami) won the respective voting for the American League and National League, earning appearances in MLB’s “Mid-Summer Classic.”[4]

After nearly 25,000 tweets in the final hour of voting, Kansas City Royals third baseman Mike Moustakas (#VoteMoose) and St. Louis Cardinals starting pitcher Carlos Martinez (#VoteTsunami) won the respective voting for the American League and National League, earning appearances in MLB’s “Mid-Summer Classic.”[4]

Following the successful All-Star campaign, Major League Baseball debuted its “MLB Clubhouse” mobile application during the 2015 playoffs enabling fans to send each other game clips and player emojis.[5] Third parties, such as SportsManias,[6] have since developed applications with emoji keyboards featuring athletes from other professional sports, including basketball, football, soccer, and hockey.[7] SportsMania’s football keyboard, for example, includes 36 emojis consisting of the “NFL’s biggest stars with a little semi-humourous [sic] touch whether it be a reference to their nickname or an attribute reflecting their personality.”[8] SportsMania’s application, while including a player’s team colors in its emojis, noticeably omits official trademarked team logos.[9]

SportsMania’s mobile app includes emojis depicting NFL stars like Carolina Panthers quarterback Cam Newton known for his “Superman” touchdown celebration.

SportsMania’s mobile app includes emojis depicting NFL stars like Carolina Panthers quarterback Cam Newton known for his “Superman” touchdown celebration.

The popularity of emojis in modern communication provides economic opportunities for application creators. In December 2015, E! Network reality star Kim Kardashian proved a commercial market exists for celebrity emojis after her $1.99 “KIMOJI” application crashed Apple’s online app store within minutes.[10] On June 2, Steph Curry debuted his $1.99 “Stephmoji” application in advance of the NBA Finals taking over the top spot on Apple’s store from Kardashian.[11] Even if third party creators offer emoji platforms for free, incentivizing downloads increases the application’s attractiveness to advertisers. Likewise, such applications may threaten the market for official league-sponsored applications if consumers find third party emojis more entertaining. Given professional sports leagues’ interest in protecting their intellectual property,[12] leagues and athletes may claim that third party application creators violate athletes’ “right of publicity” in creating an emoji in their likenesses.

The right of publicity is a state-law intellectual property right that allows an individual “to control the commercial use of his or her identity,” including his or her name, image, voice, likeness, or other identifying element of his or her persona.[13] A violation of an individual’s right of publicity represents a commercial tort of unfair competition.[14] In states that have adopted the Restatement (Third) of Unfair Competition, an individual bears the burden of establishing the following elements to succeed in their claim: (1) the defendant used the plaintiff’s identity; (2) the identity has commercial value; (3) the commercial value is appropriated for the purpose of trade; (4) the plaintiff did not consent; and (5) the appropriation resulted in commercial injury.[15] Defendants may present viable First Amendment defenses.[16]

Following the Restatement’s guidelines, professional athletes may very well have a claim against third party emoji application creators like SportsManias:

- Plaintiff Identity: Establishing the use of athlete identities may be a hurdle for athletes in presenting a claim against third party application creators since emojis are not perfect images of the athletes; the most obvious use of an individual’s likeness remains the use of a photograph or video of the individual. Athletes would still have a strong case, however, given successful litigation against EA Sports for their depiction of athletes in their NCAA Football and NCAA Basketball franchises, which included avatars with “uniquely identifiable idiosyncratic characteristics.”[17] Further, SportsMania’s advertisement of emojis of particular athletes dramatically weakens any defense that the emojis are not in the athletes’ likenesses.[18]

- Identity Commercial Value: Professional athlete identities maintain lucrative commercial value. Collectively as members of player unions, athletes license their identities for television contracts, merchandise, video games, and other revenue streams. Individual athletes, particularly those who would be featured as emojis, have additional opportunities to license their likenesses for endorsements and appearance agreements.

- Commercial Value Appropriated for Trade: Not only must an identity have commercial value, but the specific use must also be for commercial purposes. If a third party application creator offers their emojis at cost or earns advertising revenue through the application, it may well qualify as utilizing the likenesses for trade.

- Lack of Plaintiff Consent: Athletes only have a claim against emoji creators if they did not authorize third party companies to create emojis in their likenesses. Athletes likely consent to leagues using their likenesses per the terms in their respective league collective bargaining agreements (thus creating league interest in protecting athletes’ right of publicity), but do not likely consent to third party use given the monetary stakes.

- Commercial Injury: Athletes must show that the use of their likenesses harms them commercially. Athletes may be able to show commercial harm through consumer testimony that third party applications diminish the market for league sponsored applications where players would be entitled to share revenues per collective bargaining agreements. Further, any third party profits from the applications may be relevant in establishing commercial injury. The profitability of Kim Kardashian’s application enhances the claim of commercial harm in unauthorized creations.

While third party emoji creators can challenge each of the aforementioned elements, their best defense may be asserting an affirmative First Amendment “transformative use” defense. The “transformative use” test analyzes whether a work “adds significant creative elements so as to be transformed into something more than a mere celebrity likeness or imitation.”[19] More creative works that depart from a celebrity’s likeness are more likely to receive First Amendment protection. While the defendants would emphasize the creative elements in constructing emojis presumably from scratch, the plaintiffs would argue that the marketability of the emojis derives from their fame.

Ultimately, the rise of emojis as an integral part of modern communication suggests that in addition to athletes, other public figures may seek protection from third party emoji application creators. As athletes and celebrities seek to capitalize off of the market, third party emoji creators may soon find themselves in legal trouble.