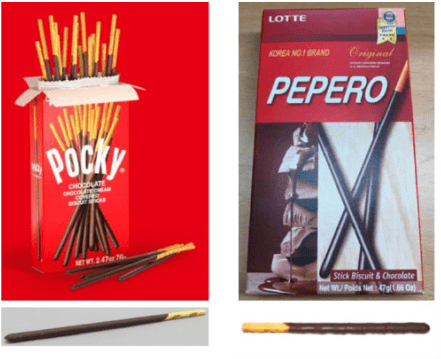

On October 8, 2020, the Third Circuit ruled against Ezaki Glico, the Appellant-Plaintiff, in a trade dress infringement case.1 Ezaki Glico (“Ezaki”), a Japanese confectionery company, claimed that its competitor, Lotte, infringed its trade dress for Pocky, the popular pencil-shaped cookies dipped in chocolate, by manufacturing Pepero, a similarly-shaped cookie product. Here is a photo of the two products for comparison:

(Image obtained from the case opinion.)

This ongoing cookie battle has been baking since 1993, when Ezaki first sent letters to Lotte asking them to stop selling Pepero.2 In response, Lotte promised that it wouldn’t manufacture more Pepero cookies but proceeded to make them anyway.3 Ezaki remained silent until 2015 when it brought this suit against Lotte.4 The district court granted summary judgment in this dessert dispute, finding Pocky’s trade dress was functional.5 The Third Circuit reviewed this decision.

Trade dress is considered a symbol or mark under the Lanham Act and, therefore, receives similar protections to that of trademarks.6 Trade dress is defined as the “total image and overall appearance” of a product and can include elements such as “size, shape, color or color combinations, texture, [and] graphics.”7 Thus, a product’s shape or configuration can be registered as its trade dress. A trade dress must be distinctive and not functional to be eligible for valid protection under the Lanham Act.8 Ezaki successfully registered two trade dresses for two Pocky configurations on the Principal Register, creating a presumption of validity.9 To rebut such validity, Lotte had to prove that the trade dresses were functional.10

Functionality can invalidate a trade dress registration because the purpose of trademark protection is to help identify the source of a product, not to give patent-like protection to useful product design.11 Patents have their own system to protect useful innovations, and trademarks cannot encroach upon this system to give companies a perpetual monopoly over product features.12 Ezaki argued that the test for functionality should be whether a design is “essential,” rather than “useful.”13 The Third Circuit disagreed, finding that if some feature of the design is useful—such as it improves cost, quality, or something similar—it is not protectable as trade dress because it is functional.14 Functionality can be shown by: 1) direct evidence that a feature or design makes the product work better, 2) a product’s maker showcasing its usefulness, 3) the existence of a utility patent, and 4) the existence of a limited number of ways to design a product.15 Ezaki’s trade dresses claim elongated rods comprising of biscuits that are partially covered on top with chocolate, almonds and chocolate, or cream.16 Ezaki argued that none of the features in the trade dresses were functional because they were not essential to make the biscuit easy to eat.17 The Third Circuit rejected this argument and instead sided with Lotte by applying the usefulness test.18

The Third Circuit analyzed all four factors stated above. First, Lotte produced direct evidence that Pocky’s features were designed to help with holding, eating, and packing the snack.19 Ezaki’s internal documents revealed that Ezaki set out to make a snack that people could eat without leaving a chocolate residue on their hands.20 Ezaki recognized that the stick shape makes Pocky easily to be held and shared.21 Second, Lotte produced evidence that Ezaki promoted Pocky’s “convenient design” and specifically touted its design features.22 Third, the Third Circuit found that Ezaki’s utility patent was irrelevant to the functionality issue.23 Lastly, while Ezaki argued that Lotte could have produced their cookies in an alternative design, the Third Circuit found that the existence of other design possibilities could not overcome the evidence of Pocky’s functionality.24

Overall, the Third Circuit found that Ezaki’s Pocky design features were purely functional and could not be validly protected as a trade dress. The features of the Pocky biscuit are not purely ornamental; namely, they serve a useful purpose instead of merely serving to identify Ezaki as the producer of Pocky.25 Accordingly, the Third Circuit affirmed the district court’s decision in favor of Lotte, settling this bitter, not sweet, dispute for the moment.

Featured Image Credit: © User:Janine / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-3.0 / Flickr

- See Ezaki Glico Kabushiki Kaisha v. Lotte Int’l Am. Corp., No. 19-3010, 2020 U.S. App. LEXIS 31926, at *16 (3d Cir. Oct. 8, 2020). ↩

- Id. at *3. ↩

- Id. ↩

- Id. ↩

- Id. at *4. ↩

- Wal-Mart Stores v. Samara Bros., 529 U.S. 205, 209 (2000). ↩

- TMEP § 1200.02 (Oct. 2018). ↩

- Wal-Mart Stores, 529 U.S. at 210. ↩

- Ezaki, 2020 U.S. App. LEXIS 31926, at *12. ↩

- Id. ↩

- See Ezaki, 2020 U.S. App. LEXIS 31926, at *6–7; see also Bill Donahue, Cookie Shape Is Not Protected By TM Law 3rd Circ. Says, Law360 (Oct. 8, 2020, 8:27 PM), https://www.law360.com/delaware/articles/1318322/cookie-shape-is-not-protected-by-tm-law-3rd-circ-says-. ↩

- See Ezaki, 2020 U.S. App. LEXIS 31926, at *7–8. ↩

- Id. at *7. ↩

- Id. at *9–10. ↩

- Id. at *11. ↩

- Id. at *12. ↩

- Id. ↩

- Id. at *12–15. ↩

- Id. at *12–13. ↩

- Id. ↩

- Id. at *13. ↩

- Id. at *13–14. ↩

- Id. at *14–15. ↩

- Id. at *14. ↩

- Id. at *13. ↩