How often do we see celebrities repost photos of themselves taken by others, or designers post photos of others wearing their designs? Did these “re-posters” ask for permission? Did they need to? On September 18, 2020, the District Court for the Southern District of New York said yes—specifically, the failure to seek permission subjects one to liability for copyright infringement.1

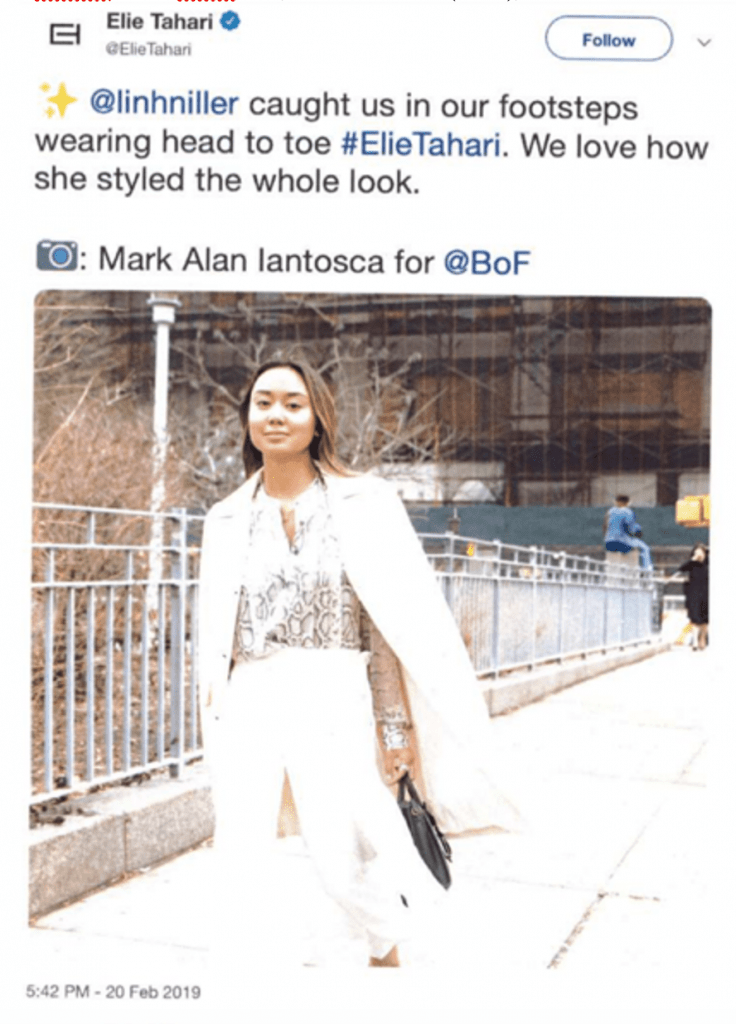

Elie Tahari, Ltd., a luxury fashion brand, hired content creator and stylist Linh Niller to wear Tahari’s clothing at Fashion Week.2 On her way to the Tahari Show, Niller was photographed by Mark Iantosca, a professional photographer.3 The copyright for the photograph was then registered on April 28, 2019.4 Upon seeing the photograph, Tahari reposted the image in a tweet (below) commenting on Niller’s look.5 However, Tahari did not obtain permission prior to reposting the photograph or otherwise obtain a license.6 Iantosca then sued Tahari for copyright infringement, and, in response, Tahari asserted three affirmative defenses, none of which the Court found convincing.7

(image attached to Plaintiff’s complaint as Exhibit B)

First, Tahari unsuccessfully tried to assert fair use.8 In determining whether an alleged infringement is fair use, Section 107 of the Copyright Act directs courts to consider the following factors: “(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.”9 Tahari asserted that its use was both transformative and non-commercial, favoring fair use, because it did not repost the photograph “in order to generate sales, or to direct customers to its site.”10 Tahari argued instead that it merely commented on the photograph of Niller wearing head-to-toe Tahari to the show.11 Contrary to Tahari’s assertions, the Court found that its use was not transformative because it did not “add ‘new insights and understandings’ for the ‘enrichment of society,’”12 and that Tahari failed to demonstrate that its use was actually “anything other than a ‘commercial use’ intended to advertise and sell its clothing.”13 Since Tahari did not make any modification to the photograph but merely reposted the creative work in the whole without a license, all factors ultimately weighed against fair use.14

Second, Tahari attempted to argue that its “use of the Photograph [was] de minimis simply because reposting another’s picture has become commonplace on social media.”15 “A de minimis use is one so trivial that ‘the law will not impose legal consequences.’”16 While hopeful marketing teams often make this argument to their in-house legal teams, the Court did not find it remotely convincing.17 In fact, Judge Vyskocil stated that “[t]here is nothing ‘trivial’ about a business utilizing a professional photographer’s work to promote its products” and that if such an argument were accepted, it would signal a “seismic shift in copyright protection.”18

Finally, Tahari tried to argue that its use of Iantosca’s photograph was not infringing because Tahari attributed credit to Iantosca.19 The Court found such an assertion to be without merit because attribution is not a defense against copyright infringement.20 Also, the Court stated that the originality of the photograph, which renders copyright protection for the work, stems from Iantosca’s artistic decisions, such as lighting, lens, and angle.21 Any argument by Tahari that Niller was wearing Tahari-branded clothing was irrelevant to any copyright infringement liability.22

Although the exact damages are yet to be determined, this decision should serve as a reminder to all social media users to obtain permission prior to reposting an image, particularly those operating accounts for large companies. The fact that “everyone else is doing it” or that a photograph captures you or your company’s products is not a defense to copyright infringement.

- Iantosca v. Elie Tahari, Ltd., No. 19-cv-04527 (MKV), 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 171512 (S.D.N.Y. Sep. 18, 2020). ↩

- Def.’s Mem. of Law in Opp’n to Pl.’s Mot. For Summ. J., at 6. ↩

- Elie Tahari’s Reposting of Street Style on Social Media is Not “Trivial” or Fair Use, The Fashion Law (Sept. 24, 2020), https://www.thefashionlaw.com/elie-taharis-reposting-of-photo-on-social-media-is-not-trivial-or-fair-use/. ↩

- Iantosca, 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 171512, at *2. ↩

- Elie Tahari’s Reposting of Street Style on Social Media is Not “Trivial” or Fair Use, supra note 3. ↩

- Iantosca, at *4. ↩

- Id. at *12–16. ↩

- Id. at *4. ↩

- 17 U.S.C. § 107 (2018). ↩

- Def.’s Mem. of Law in Opp’n to Pl.’s Mot. For Summ. J., at 6. ↩

- Id. ↩

- Iantosca, at *13. ↩

- Id. ↩

- Id. at *13–14. ↩

- Id. at *14–15. ↩

- Id. at *8 (quoting On Davis v. Gap, Inc., 246 F.3d 152, 175 (2d Cir. 2001)). ↩

- Gonzalo E. Mon & Michael Zinna, New Decision Warns Against Reposting Photos on Social Media, Ad Law Access (Sept. 23, 2020), https://www.adlawaccess.com/2020/09/articles/new-decision-warns-against-reposting-photos-on-social-media/. ↩

- Iantosca, at *14–15. ↩

- Id. at *15. ↩

- Id. ↩

- Id. at *15–16 (citing Mannion v. Coors Brewing Co., 377 F. Supp. 2d 444, 452 (S.D.N.Y 2005)). ↩

- Id. at *16. ↩