In January 2018, Jason “Revok” Williams served a cease and desist notice on H&M, the Swedish retail company, contending that the advertisement for its “New Routine” sportswear line infringed a copyright he owned. 1 The copyright Revok referred to was an unsanctioned graffiti spray-painted on a wall in the William Sheridan Playground in Brooklyn, New York. 2 H&M in its reply denied all claims of infringement, contending instead that no copyright could exist in an unauthorized work. Unable to resolve the issue, the clothing giant decided in March 2018 to file a suit in the Eastern District Court of New York seeking a declaration that its advertisement does not infringe upon the defendant’s copyright. 3 The lawsuit prompted a nationwide social outrage that forced H&M to reevaluate its strategies and subsequently withdraw the suit and issue a formal apology. 4 Unfortunately for us, without a judicial pronouncement addressing this extremely interesting factual milieu, a lot of questions remain unanswered.

Was The Graffiti Eligible For Copyright Protection?

Under the copyright laws of the U.S., copyright protection is extended to original works of authorship that are fixed in a tangible medium of expression. 5 The originality requirement is satisfied when the work is 1) independently created and 2) bears a modicum of creativity. 6 In the case at hand, fixation should not be an issue as the graffiti has been painted on a wall and is thus sufficiently permanent to be perceived by viewers for more than a transitory duration. 7 The second criterion of originality can be better understood if we take a closer look at the design employed by Revok. Since the design is his own, i.e. not copied from another, it can be said to be independently created. Further, we see that the graffiti is a three-dimensional portrayal of a series of black lines that ascends and descends in a pattern. The design is thus intricate and creative, satisfying the low originality threshold required by courts. The graffiti, having satisfied all factors of copyrightability, should reasonably be eligible for protection as an artistic work.

Can a Copyright Exist in An Illegal Work?

For at least forty years, appellate courts have rejected claims that works that are illegal because they are, for example, prohibited as obscene, they are not protected by copyright. As the Fifth Circuit stated in Mitchell:, “In our view, the absence of content restrictions on copyrightability indicates that Congress has decided that the constitutional goal of encouraging creativity would not be best served if an author had to concern himself not only with the marketability of his work but also with the judgment of government officials regarding the worth of the work.” 8 Therefore, copyright is understood to be content neutral. 9 Even if the work is illegal or unauthorized, as in this case, the copyright that subsists in it since the moment of its inception, is not taken away. Here, of course, the argument is not that that the work’s content is unlawful, but that its fixation was illegal. However, as Celia Lerman has argued, a distinction must be drawn between the protected intangible right in the graffiti and its physical embodiment 10 Thus, even if the graffiti on the wall was unauthorized, such illegality only attaches itself to the copy on the wall while the copyright in the intangible artistic work remains with the author. The painting of the graffiti, whether looked at from an angle of content illegality or of an unauthorized fixation, does not take away the copyright that inherently subsists in it.

Is it Copyrightable Even if It’s in The Public Space?

An extremely common misconception harbored by many people is that “works in the public space” and “works in the public domain” are one and the same. 11 Works in a public space are copyrightable works that are displayed or showcased in areas that are open to public viewing, whereas works in the public domain are works that are not entitled to protection under the Copyright Act. This is either because the copyright has expired or the author has dedicated the work to the public domain. 12 Thus, a graffiti like the one in our case is a copyrighted work that is located in a public space. Merely because the work is accessible by people, its copyrightability is not taken away or in any way diminished. This means that H&M could not have used it as part of its advertisement campaign simply because it was out in the open.

Was There Copyright Infringement?

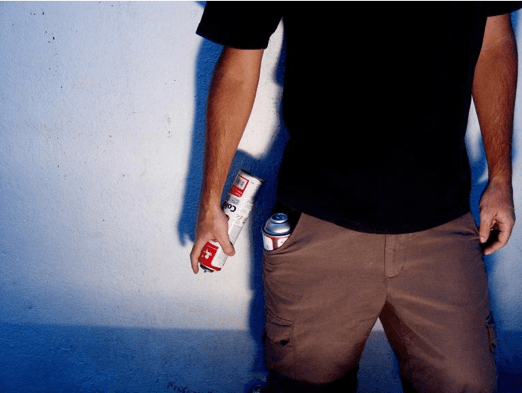

Usually, in a claim of copyright infringement, a twofold test of 1) copying in fact and 2) improper appropriation needs to be proved by the plaintiff. 13 However, it seems that H&M admitted that it copied Revok’s work and in any case, it could hardly deny that it did, since there exist “striking similarities” between Revok’s work and the graphic that appears in the H&M advertisement – they are identical. 14 Coming to the next factor, improper appropriation requires that the infringers take more than what was permitted, i.e. they appropriate for their own use what was not theirs. 15 Here, a possibly strong defense that H&M can come up with is that the usage of the graffiti was de minimis. This exact rationale was successfully employed in Gottlieb wherein one of the scenes in the movie “What Women Want” had a Silver Slugger pinball machine. Similar to the case at hand, the producers of the movie had not sought permission of the copyright owners of the pinball machine and hence were subjected to an infringement suit. 16 This defense was once again successfully employed in Gayle, where a nearly identical issue of copyright infringement of a graffiti came up before the court. 17 However, it is very unlikely that this defense of de minimis copying would be as successful for us. Here, the graffiti features prominently in the advertisement with a man back flipping in front of it. The graffiti is clearly visible throughout the video and is never out of focus. Further, it looks like the graffiti has been deliberately used to give a gritty vibe to the otherwise chic clothing brand. An element that forms such a vital part of the advertisement can surely not be considered insignificant. The placement, focus and duration are all indicative of the improper appropriation. It is quite likely that a court could have found H&M guilty of copyright infringement. Even the defense of fair use, employed by the Court in Seltzer would be inapplicable here as the advertisement would most likely be seen as commercial and non-transformative. 18

All in all, we see that Jason Revok Williams, despite the nature of the work involved and the illegality that surrounded it, had a pretty strong claim of copyright infringement, one which H&M had the better sense of withdrawing from.

- Sonia Rao, H&M’s battle with the artist Revok shows how street art is being taken seriously, THE WASHINGTON POST (Mar. 16, 2018), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/arts-andentertainment/wp/2018/03/16/hms-battle-with-the-artist-revok-shows-how-street-art-is-being-taken-seriously/?utm_term=.579a36bfd232. ↩

- Jenna Amatulli, People Are Boycotting H&M over Alleged Infringement of an Artist’s Graffiti, HUFFINGTON POST (Mar. 15, 2018), https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/hm-boycott-graffiti-copyrightinfringement_us_5aaa835ce4b045cd0a6f5083. ↩

- Keith Estiler, Update: H&M Files Lawsuit against Graffiti Artist, Denies Copyright Protection, HYPEBEAST (Mar. 15, 2018), https://hypebeast.com/2018/3/hm-revok-copyright-infringement-case. ↩

- Lia McGarrigle, H&M Drops Lawsuit against REVOK Claiming Illegal Graffiti Doesn’t Have Copyright Protection, HIGHSNOBIETY (Mar. 15, 2018), https://www.highsnobiety.com/p/hm-graffiti-coyright-lawsuit/. ↩

- 17 U.S.C. § 102 (2018). ↩

- Feist Publication, Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service Co., 499 U.S 340, 345 (1991). ↩

- Cartoon Network LLP v. CSC Holding, Inc., 536 F.3d 121, 128 (2008). ↩

- Mitchell Brothers Film Group v. Cinema Adult Theater, 604 F.2d 852, 856 (5th Cir. 1979). ↩

- Neil Weinstock Netanal, Locating Copyright within the First Amendment Skein, 54 STAN. L. Rev. 1, 48, 54-59 (2001). ↩

- Celia Lerman, Protecting Artistic Vandalism: Graffiti and Copyright Law, 2 N.Y.U. J. INTELL. PROP. & ENT. L. 295, 317 (2013). ↩

- David Gonzalez, Walls of Art for Everyone, but Made by Not Just Anyone, N.Y. TIMES (June 4, 2007), http://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/04/nyregion/04citywide.html. ↩

- Timothy Vollmer, The public domain and 5 things not covered by copyright, CREATIVE COMMONS (Jan. 16, 2017), https://creativecommons.org/2017/01/16/public-domain-5-things-not-covered-copyright/. ↩

- Arnstein v. Porter, 154 F.2d 464, 469 (2nd Cir. 1946). ↩

- Id. at 468. ↩

- Id. at 473. ↩

- Gottlieb Development LLC v. Paramount Pictures Corp., 590 F.Supp. 2d 625, 629 (S.D.N.Y 2008). ↩

- Itoffee R. Gayle v. Home Box Office Inc., 17-CV-5867, 2018 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 73254 (S.D.N.Y May 1, 2018). ↩

- Seltzer v. Green Day, Inc., 725 F.3d 1170, 1173 (9th Cir. 2013). ↩

Love this article! Interesting to see how public works of art are not entirely “public”.