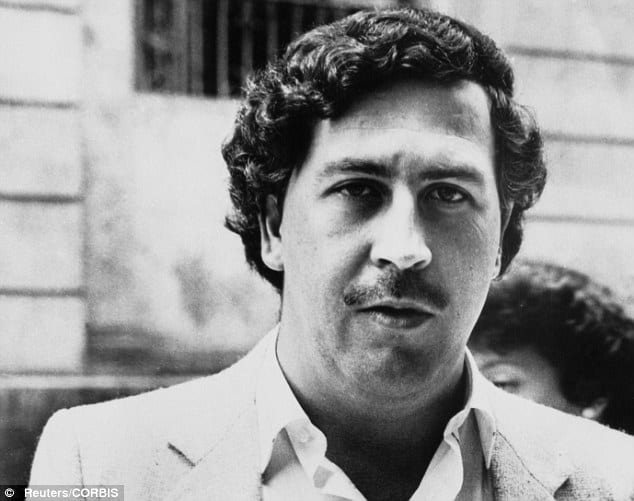

I finished season one of Netflix’s Narcos, but Rodrigo Amarante’s hypnotic theme song “Tuyo” continues to play on in my head weeks later. Narcos dramatizes the rise and fall of the Colombian “King of Cocaine” Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria and the drug war between the DEA and the Medellín drug cartel in the ‘80s. My anticipation for Narcos’ season two release and my interest in all things related to trademarks left me wondering whether the world of Pablo Escobar ever intersected with intellectual property. Sure enough—in true Escobar form— “Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria” clashed with the Colombian government in an intellectual property battle in Bogotá in 2013.

Two years ago, the Colombian government denied the request of Pablo Escobar’s family to trademark his name (alongside his fingerprint and signature) in their native Colombia for services in Class 41, including education and entertainment. Escobar’s family members argued that the proposed trademark “sought to convey messages that invite reflection of humanity, hoping to generate a moral consciousness and morality.”[i]

The Commission of Industry and Commerce (CICC) of Colombia, however, rejected the mark, claiming that to grant the trademark registration would “offend [the] morality of Colombian society and public order.”[ii] The CICC added that the mark “makes apology for violence and undermines public order, especially when taking into account the purpose of the services intended to protect, such as education, training and entertainment.”[iii] In defense of the CICC decision, Jose Luis Londono, delegate of industrial property for the superintendent of industry and commerce in the Colombian capital Bogotá, said, “It’s like you went to Germany and tried to create a brand called Hitler.”[iv]

Despite the denial of the Class 41 application, “PABLO EMILIO ESCOBAR GAVIRIA” is actually an internationally registered trademark, including at the USPTO, for goods in Class 25.[v] In 2010, Pablo Escobar’s son, Sebastián Marroquín (formerly Juan Pablo Escobar Henao), launched his clothing line, Escobar Henao. Named after Marroquín’s original paternal and maternal last names, the line includes t-shirts emblazoned with Pablo Escobar’s various forms of identification, from his international driving license to his Colombian citizenship card.[vi] Marroquín also holds a registered trademark for “ESCOBAR HENAO.”[vii]

Escobar Henao is currently sold in Mexico, the United States, Austria, Puerto Rico and Guatemala.[viii] While Marroquín’s pieces are produced in Medellín, they are not sold in Colombia out of respect to Escobar’s victims. Marroquín admits that his clothing venture is somewhat paradoxical given that his father’s image embodies both strength and violence, however, through Escobar Henao, Marroquín aims to send a message of peace and reflection about his father’s personal history.[ix]

On the one hand, Marroquín rightly believes he has the right to exploit his father’s image, unlike others who have made money off of his father´s life by writing books and producing TV series.[x] “I wanted to register my father’s name [as a brand] to protect it from bad usage, manipulation and profit-making by the Colombian government and the media who are making up stories.”[xi] Yet, on the other, Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria’s name is still “associated with a cycle of violence which crossed Colombia in the eighties and nineties, leaving thousands of victims behind.”[xii] According to official estimates, the Medellín drug cartel perpetrated 4,000 murders.[xiii]

As The World Trademark Review succinctly sums it up: “For families looking to protect or profit from the name of an (in)famous relative, there is a delicate balancing act between the right of publicity and registering a mark that offends morality.”[xiv]