Introduction

As virtually every part of life now takes place online, there is a need for national cybercrime legislation to ensure uniform policing and implementation.[1] Currently, the amended Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (“CFAA”), 18 U.S.C. § 1030, “prohibits unauthorized access—or exceeding authorized access—to protected computers and networks.”[2] Congress passed the original CFAA bill in 1984 as the “Counterfeit Access Device and Computer Fraud and Abuse Act,” first amended as the CFAA in 1986, and has since amended the CFAA as recently as 2008.[3]

Compared to other computer crime statutes, the Congressional Research Service notes: the “CFAA deals with computers as victims; other laws deal with computers as arenas for crime or as repositories of the evidence of crime or from some other perspective.”[4] Much of the CFAA overlaps with other espionage, fraud, and theft provisions, as there are over forty laws relating to cybersecurity.[5]

The CFAA

The current statute defines its scope in multiple sections: Section (a) outlaws seven types of crimes that will be outlined infra, Section (b) outlaws conspiracy to commit the above crimes, Section (c) delineates penalties for violations, and Section (e) defines common terms in the statute.[6] The remaining sections outline the related authorities, application to law enforcement, and civil cases.[7]

Subsection 1030(a)(1) specifically outlaws “access[ing] a computer” to commit espionage with the purpose of tracking existing espionage laws.[8] Under this subsection of the statute, for a defendant to be convicted of national security cybercrime, the defendant must “(1) purposefully transmit or retain information that (2) he has reason to believe could be used to the injure the United States or benefit another country, and (3) that he has obtained through access to a computer that he knows he had no authority to access.”[9]

Subsection 1030(a)(2) outlaws obtaining information where “the defendant (1) intentionally (2) accessed without authorization (or exceeded authorized access to) a (3) protected computer and (4) thereby obtained information.”[10] The three categories of protected computers are computers used by a financial institution, computers used by the the United States government, and computers “used in or affecting interstate or foreign commerce or communication.”[11] Courts struggle with the interpretation of what constitutes “without authorization” or “exceeds authorized access.”[12] Subsection 1030(a)(2) is “unique” from other fraud and theft conversion statutes in that it “requires no larcenous intent.”[13]

Subsection 1030(a)(3) outlaws computer trespassing in a federal government computer, specifically for anyone “without authorization . . . intentionally . . . access[ing] a government computer [either] maintained exclusively for” or “used, at least in part, by . . . the federal government.”[14] The Congressional Research Service distinguished 1030(a)(2) and 1030(a)(3) stating: “[p]aragraph 1030(a)(2) is essentially paragraph 1030(a)(3) plus an information acquisition element and a broader jurisdictional base.”[15]

Subsection 1030(a)(4) outlaws fraud related to protected computers where the defendant “access[ed] a protected computer without authorization or exceeding authorization” with the “intent to defraud” and “thereby furthering a fraud and obtaining anything of value.”[16] Congress amended this to include computers used by or for the government, a financial institution, or affecting interstate or foreign commerce.[17]

Subsection 1030(a)(5) outlaws “damag[ing]” a government computer, a bank computer, or a computer used in, or affecting, interstate or foreign commerce with a dual intent requirement “to knowingly or intentionally intrude, and intent to [cause] damage.”[18] A key difference from other subsections is that it has no “exceeds authorization” element, just an “unauthorized access” element.[19]

Subsection 1030(a)(6) outlaws the “trafficking [of]… a computer password… or key… knowingly and with an intent to defraud” with regard to either “a federal computer” or one “that affects interstate or foreign commerce.”[20] The vague language regarding protecting computers that belong to a “department or agency of the United States” make it unclear if this phrase refers just to the executive agencies or to all three branches of government.[21]

Finally, subsection 1030(a)(7) outlaws extortion through “threat[s] to cause damage to a protected computer” as well as other computer related threats.[22] Congress expanded this subsection in 2008 to criminalize threats regarding stealing data, publicly disclosing stolen data, or not repairing the already caused damage.[23] This provision has a higher mens rea requirement of “with intent to extort” rather than “knowingly and with an intent to defraud” in an attempt to avoid uncertainty in the statute.[24]

Section (e) defines a “protected computer” as a computer either “(A) exclusively” or partially “use[d by] the United States government” or a “financial institution,” or “conduct” on a computer that “affects that use by or for the financial institution or the Government;” or “(B) which is used in or affecting interstate or foreign commerce or communication.”[25]

The CFAA defines the term “exceeds authorized access” as “access[ing] a computer with authorization and [ ] us[ing] such access to obtain or alter information in the computer that the accessor is not entitled so to obtain or alter” but does not define “with authorization.”[26] The DOJ notes that legislative history indicates a person who exceeds access is an insider and those without authorization are outsiders.[27]

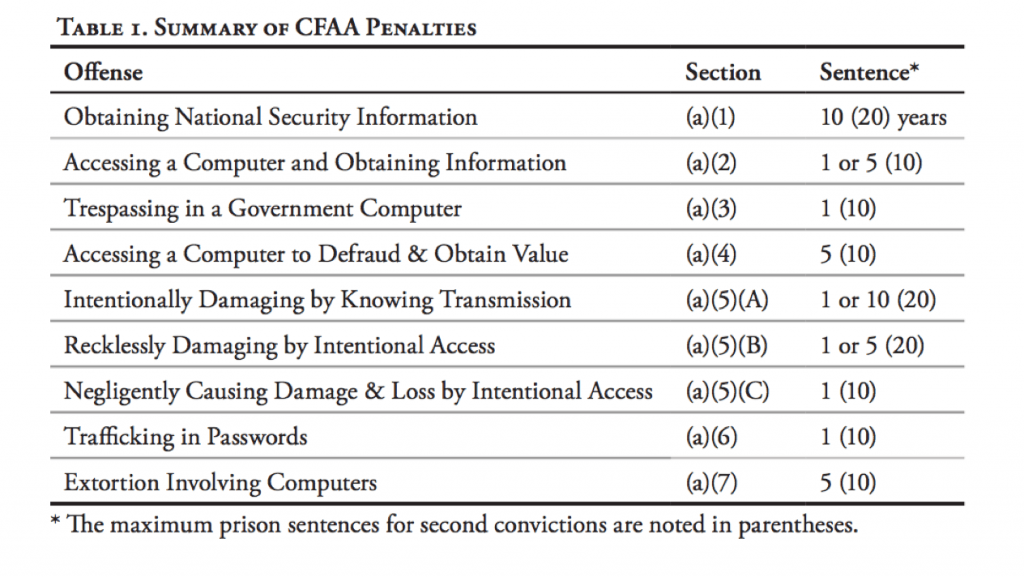

The Department of Justice noted Congressional intent “to strike an ‘appropriate balance between the Federal Government’s interest in computer crime and the interests and abilities of the States to proscribe and punish such offenses.’”[28] The Department of Justice created a chart to summarize CFAA Penalties:

Figure 1[29]

Inconsistent Judicial interpretation of the CFAA

Judicial interpretation and cases illustrate the flaws in the CFAA and the need for clarification and a twenty-first century solution.[30] There are two camps of judicial interpretation: those who apply the CFAA broadly to include violating written rules like terms of service or trade secrets and those who read it narrowly to include only software violations like hacking.[31]

On the one hand, “[t]he First, Fifth, Seventh and Eleventh Circuits apply the [CFAA]… broadly [to] allow[ ] remedies or enforcement based on the theft or destruction of data” and consider “whether the conduct involves a breach of duty of loyalty or a non-business purpose or is contrary to non-disclosure or use terms.”[32] This is demonstrated in cases like EarthCam, Inc. v. OxBlue Corp. where the Eleventh Circuit held that “although it is not entirely clear . . . a person exceeds authorized access if he or she uses the access in a way that contravenes any policy or term of use governing the computer in question.”[33] Many advocates note that the phrase “although it is not entirely clear” indicates why the CFAA needs amendments and clarification.[34]

On the other hand, the Second, Fourth, and Ninth Circuits apply the CFAA narrowly by focusing on whether the original authorized access to network was restricted or rescinded, and generally agree that violations of terms of service does not violate the CFAA.[35]

The Ninth Circuit emphasized in United States v. Nosal that “we have held that authorization is not pegged to website terms and conditions. . . . This provision, coupled with the requirement that access be ‘knowingly and with intent to defraud,’ means that the statute will not sweep in innocent conduct, such as family password sharing.”[36] In an earlier appellate hearing for Nosal, the Ninth Circuit found that the legislative history only supports “punish[ing] hacking—the circumvention of technological access barriers” because Congress has other trade secret legislation.[37]

Recent Critiques of the CFAA

While Congress attempted to pass national legislation amending or replacing the CFAA, recent proposals have not succeeded.[38] The general areas of focus in the proposed legislation include “information sharing . . . responsibilities and authority of federal agencies,” theft and fraud, and the “offenses and penalties [of] cybercrime.”[39] Additionally, the CFAA should follow the Second, Fourth, and Ninth Circuit’s opinions and define “gaining unauthorized access” as “circumventing technological or physical controls.”[40]

Many criticize the CFAA as overbroad and outdated.[41] Proponents for change argue the CFAA allows prosecutorial abuse in interpretation because it is too vague without adequate definitions.[42] For example, it “makes it a federal crime to access a computer without authorization or in a way that exceeds authorization” without describing what this entails.[43] Another criticism is the “redundant provisions…enable a person to be punished multiple times… for the same crime . . . play[ing] a significant role in sentencing.”[44] Attempted amendments like Aaron’s Law sought to “distinguish the difference between common online activities and harmful attacks.”[45] For example, sponsors introduced Aaron’s Law first in 2013, and again in 2015, to reform prosecutorial misuse and redundant provisions that led an internet activist Aaron Swartz to die by suicide because he faced multiple felony charges under CFAA for downloading academic articles.[46]

The main criticisms that would be rectified in these failed bills include lessening punishment for minor offenses, which, at present, may receive the same punishment as computer terrorism for something as simple as violating a vendor’s terms of agreement.[47] Currently, “[l]ying about one’s age on Facebook, or checking personal email on a work computer, could violate this felony statute.”[48]

Proposed Solutions to the CFAA

But how do we update a thirty-year-old statute to better reflect the twenty-first century? Practitioners call for reform because of the inconsistent application of the CFAA between the circuits, as the Second, Fourth, and Ninth favor a narrow interpretation with a focus on original access restriction or recension, and the First, Fifth, Seventh and Eleventh Circuits favor broad interpretation with a focus on breaches of loyalty, non-disclosure, or terms of use.[49] The purpose of a statute is to put the public on notice as to what behavior would violate the statute, and that is currently unclear under the CFAA.[50]

To resolve this, Congress has a few options: there are many proposals to change and improve the CFAA.[51] While some argue Congress could “empower an administrative agency to create rules regulating the activity,” others argue for amending the CFAA for clarity.[52] The Electronic Frontier Foundation, a leader in expanding competition and consumer protections in the cybersphere, published its own proposals to amend Aaron’s Law to better combat the issues with the CFAA.[53] The overall consensus points to reforming the definitions and standards of the CFAA.[54]

Proposed Reforms to Definitions

As some Circuits already do to limit the scope of penalizing obtaining and misuse of information, Congress can focus on emphasizing the terms “use” or “purpose” rather than “authorization.”[55] The statute says, “without authorization” or “exceeding authorized access,” but “exceeding authorized access” inherently means the user “obtain… information… that the [individual] is not entitled” to use.[56]

Alternatively, Congress could redefine authorization with the guidance that the CFAA “applies when initial permitted access to information is later rescinded or abused.”[57] This would “establish that mere breach of terms of service, employment agreements, or contracts are not automatic violations of the CFAA.”[58] This would still ensure that phishing, malware, or viruses would still be categorized as “unauthorized access …by circumventing technological or physical controls.”[59]

Like the courts who read the CFAA narrowly, Congress could revise the law to focus on hacking rather than appropriation of trade secrets, as the legislative history only supports punishing hacking—“the circumvention of technological access barriers”—because Congress has other trade secret legislation.[60]

Proposed Reforms to Standards

The civil remedy provision of the CFAA is also in need of reform. For instance, Congress should establish a separate standard of proof for civil cases, as “the statute does not recognize common distinctions [between criminal and civil remedies, like] a higher standard for intent.”[61] Further, Congress should extend the statute of limitations from two to five years to be “comparable to the criminal provisions.”[62] Additionally, Congress should incorporate a proportionality clause to ensure that “prosecutors cannot seek to inflate sentences by stacking” state statutes and non-criminal violations against the same act.[63] Finally, Congress can establish a higher mens rea to the elements of intent or knowledge of trespass to make sure that the CFAA would only punish willful violations.[64]

Congress should apply a misappropriation standard for whether the defendant misappropriated or stole the information, focusing on “intent and circumstances of the theft” rather than “initial authorized or unauthorized access.”[65] Congress should also decriminalize certain sections of the CFAA to focus solely on civil liability.[66] But Congress should be careful to streamline the law and reduce redundancy so that a person cannot face duplicate charges for the same violation.[67]

The CFAA needs a makeover to align judicial rulings under one interpretation and limit prosecutorial misuse and misapplication of the CFAA’s overly broad definitions.[68]

[1] See generally CHARLES DOYLE, CONG. RESEARCH SERV., 97-1025, CYBERCRIME; AN OVERVIEW OF THE FEDERAL COMPUTER FRAUD AND ABUSE STATUTE AND RELATED FEDERAL CRIMINAL LAWS 1-2 (2014) (noting that the CFAA is “not a comprehensive provision, but instead it fills cracks and gaps” and that “over the last three decades, Congress has kneaded, reworked, recast, amended, and supplemented to bolster the uncertain coverage” of other relevant statutes).

[2] Kim Zetter, The Most Controversial Hacking Cases of the Past Decade, WIRED (Oct. 26, 2015, 7:00 AM), https://www.wired.com/2015/10/cfaa-computer-fraud-abuse-act-most-controversial-computer-hacking-cases/.

[3] See ERIC FISCHER, CONG. RESEARCH SERV., R42114, FEDERAL LAWS RELATING TO CYBERSECURITY: OVERVIEW OF MAJOR ISSUES, CURRENT LAWS, AND PROPOSED LEGISLATION 2 (2014); CFAA Background, NAT’L ASS’N CRIMINAL DEF. LAWYERS (Mar. 10, 2020), https://www.nacdl.org/Content/CFAABackground.

[4] DOYLE, supra note 1, at 1.

[5] See FISCHER, supra note 3, at 2-3.

[6] See Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, 18 U.S.C. § 1030.

[7] See id.

[8] See 18 U.S.C. § 1030(a)(1); DOYLE, supra note 1, at 73-74.

[9] DOYLE, supra note 1, at 75 (citing to H.R. Rep. No. 98-894 (1984)).

[10] Id. at 15 (quoting United States v. Auernheimer, 748 F.3d 525, 533 (3d Cir. 2014)).

[11] See OFFICE OF LEGAL EDUC., EXEC. OFFICE FOR U.S. ATT’YS, PROSECUTING COMPUTER CRIMES 4 (2010).

[12] See DOYLE, supra note 1, at 15-16 (quoting LVRC Holdings LLC v. Brekka, 581 F.3d 1127, 1133 (9th Cir. 2009)) (stating that “[s]ome have applied the terms to access by authorized employees who use their access in any unauthorized manner or for unauthorized purposes and to access by outsiders who have been granted access subject to explicit reservations. Others have concluded that ‘a person who “intentionally accesses a computer without authorization” §§1030(a)(2) and (4), accesses a computer without any permission at all, while a person who “exceeds authorized access,” has permission to access the computer, but accesses information on the computer that the person is not entitled to access.'”).

[13] See id. at 25.

[14] Id. at 3.

[15] Id. at 25.

[16] Id. at 50.

[17] See id.

[18] Id. at 31.

[19] See id. at 33.

[20] Note that this subsection contains the same mens rea for subsection (a)(4). Id. at 71.

[21] See id.

[22] See id. at 64.

[23] See NAT’L ASS’N CRIMINAL DEF. LAWYERS, supra note 3.

[24] See DOYLE, supra note 1, at 67.

[25] 18 U.S.C. § 1030(e)(2).

[26] 18 U.S.C. § 1030(e)(6).

[27] See OFFICE OF LEGAL EDUC., supra note 11, at 5.

[28] Id. at 1.

[29] Id. at 3.

[30] See, e.g., Zoe Lofgren & Ron Wyden, Introducing Aaron’s Law, A Desperately Needed Reform of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, WIRED (June 20, 2013, 9:30 AM), https://www.wired.com/2013/06/aarons-law-is-finally-here/.

[31] See Josephine Wolff, The Hacking Law That Can’t Hack It, SLATE (Sept. 27, 2016, 11:15 AM), https://slate.com/technology/2016/09/the-computer-fraud-and-abuse-act-turns-30-years-old.html.

[32] Mark L. Krotoski, Time to Reform the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, LAW.COM: THE RECORDER (Nov. 18, 2015, 3:44 PM), reprinted in MORGAN LEWIS: PUBLICATIONS, https://www.morganlewis.com/pubs/time-to-reform-the-computer-fraud-and-abuse-act.

[33] EarthCam, Inc. v. OxBlue Corp., 703 F. App’x 803, 808 (11th Cir. 2017) (emphasis added).

[34] See Lofgren & Wyden, supra note 30.

[35] See Michelle Mancino Marsh & Lindsay Korotkin, Ninth Circuit: Computer Fraud and Abuse Act Doesn’t Block Public Profile Data Scraping, ARENT FOX: PERSPECTIVES: ALERTS (Sept. 25, 2019), https://www.arentfox.com/perspectives/alerts/ninth-circuit-computer-fraud-and-abuse-act-doesnt-block-public-profile-data; Krotoski, supra note 32.

[36] See United States v. Nosal (Nosal II), 844 F.3d 1024, 1028 (9th Cir. 2016), cert. denied, 138 S. Ct. 314 (2017) (affirming CFAA violations under subsection 1030(a)(4) prohibiting accessing a computer to defraud or obtain value, finding former employee Nosal exceeded authorization by violating company policy when he downloaded confidential company information and used it to start a competing company).

[37] Wolff, supra note 31 (quoting United States v. Nosal (Nosal I), 676 F.3d 854, 863 (9th Cir. 2012)).

[38] See, e.g., Aaron’s Law Act of 2015, S. 1030, 114th Cong. (2015); Aaron’s Law Act of 2015, H.R. 1918, 114th Cong. (2015).

[39] FISCHER, supra note 3, at 6.

[40] Lofgren & Wyden, supra note 30 (explaining that this interpretation of the CFAA allows for “common computer and internet activity” without compromising the ability to prosecute traditional “hack attacks such as phishing, injection of malware or keystroke loggers, denial-of-service attacks, and viruses . . .”).

[41] See, e.g., Aaron’s Law Act of 2015, S. 1030; Aaron’s Law Act of 2015, H.R. 1918.

[42] See Lofgren & Wyden, supra note 30.

[43] Id.

[44] Id.

[45] Id.

[46] See Aaron’s Law Act of 2015, S. 1030; Aaron’s Law Act of 2015, H.R. 1918; see also Lofgren & Wyden, supra note 30.

[47] See James Hendler, It’s Time to Reform the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, SCI. AM. (Aug. 16, 2013), https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/its-times-reform-computer-fraud-abuse-act/.

[48] Lofgren & Wyden, supra note 30.

[49] See Krotoski, supra note 32.

[50] See id.

[51] See, e.g., Ric Simmons, The Failure of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act: Time to Take an Administrative Approach to Regulating Computer Crime, 84 GEO. WASH. L. REV. 1703 (2016).

[52] See id. at 1714.

[53] See ELEC. FRONTIER FOUND., Computer Fraud And Abuse Act Reform, https://www.eff.org/issues/cfaa (last visited Mar. 27, 2020).

[54] See, e.g., Krotoski, supra note 32.

[55] See id.

[56] 18 U.S.C. §§ 1030(a)(1), 1030(a)(e)(6).

[57] Krotoski, supra note 32.

[58] Lofgren & Wyden, supra note 30.

[59] Id.

[60] See Wolff, supra note 31 (quoting United States v. Nosal (Nosal I), 676 F.3d 854, 863 (9th Cir. 2012)).

[61] Krotoski, supra note 32.

[62] Id.

[63] Lofgren & Wyden, supra note 30.

[64] See Jonathan Keim, Updating the Consumer Fraud and Abuse Act, 16 ENGAGE 3 (Oct. 28, 2015), https://fedsoc.org/commentary/publications/updating-the-computer-fraud-and-abuse-act-1.

[65] See Krotoski, supra note 32.

[66] See Keim, supra note 64.

[67] See Lofgren & Wyden, supra note 30.

[68] See Krotoski, supra note 32.

Image courtesy of wikimedia commons.