Introduction

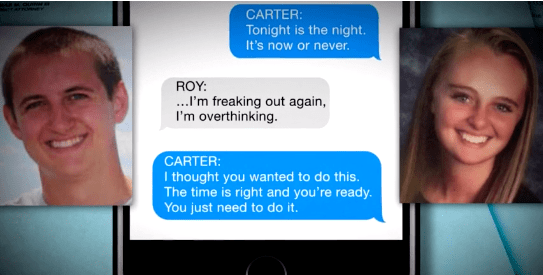

On the night of July 12, 2014, 18-year-old Conrad Roy took his life in his truck in a Kmart parking lot in Fairhaven, Massachusetts.[1] Encouraged by his girlfriend, 17-year-old Michelle Carter, Roy started a portable water pump that he placed in his truck and filled the cabin with carbon monoxide.[2] Roy had attempted to commit suicide various other times, but none of the attempts succeeded because Roy either abandoned them or sought help.[3] In a way similar to these previous abandoned attempts, during this attempt, Roy got out of the car “seeking fresh air” and called Carter.[4] Roy and Carter had a long-distance relationship for about two years, “primarily through texts and calls.”[5] Initially, Carter, “urged Roy to seek professional help for his mental illness” during this two-year relationship.[6] However, according to the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court (SJC), Carter began “a systematic campaign of coercion” to make sure that Roy went through with his suicide plan.[7] When Carter learned that Roy got out of the truck, the trial judge found that she instructed him to get back into the car, from her home 50 miles away.[8] When Roy got back into the truck, Carter failed to call either 911 or Roy’s family, and Roy died.[9]

The Massachusetts Juvenile Court trial judge ruled that Carter had engaged in wanton and reckless conduct that caused Roy’s death.[10] Carter was therefore convicted of involuntary manslaughter.[11] Carter appealed to the SJC, which affirmed the trial court’s decision.[12] Carter then petitioned for a writ of certiorari, raising two constitutional issues based on her conviction of involuntary manslaughter: (1) “[w]hether [her] conviction for involuntary manslaughter, based on words alone, violated the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment”; (2) “[w]hether [her] conviction violated the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment.”[13] The United States Supreme Court denied the writ of certiorari.[14]

The denial of this petition to be heard before the Supreme Court raises concerns in a world of rapidly increasing online social media use, especially amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, where individuals are forced to stay at home, and their main form of communication is virtual.[15] Without addressing the two constitutional issues of free speech and due process in this case, the decision by the SJC leaves poor guidance for future cases and leaves decisions to rest on subjective judgments of the prosecution and judges.[16]

First Amendment Violations

The first issue the Supreme Court should have addressed was whether Carter’s communications, which allegedly led to Roy’s suicide, constituted speech protected by the First Amendment, or if her speech was not protected because it was “used as an integral part of conduct in violation of a valid criminal statute.”[17] In Giboney v. Empire Storage & Ice, strikers participated in picketing activities while expressing their truth about the labor dispute.[18] The Court held that while the strikers engaged in speech when publicizing information about their labor dispute, they also used “their powerful transportation combination, their patrolling, [and] their formation of a picket line warning union men not to cross at peril of their union membership,” engaging in conduct that violated Missouri law and therefore was not protected by the First Amendment.[19] Here, Giboney would not apply because Carter was convicted on her words alone and was in no way physically involved like the strikers had been, as she was 50 miles away when Roy committed suicide.[20] One part of the Supreme Court’s role is to “protect[ ] [the] civil rights and liberties [of individuals] by striking down laws that violate the Constitution.”[21] The Supreme Court should not have denied the petition in this case because there is still ambiguity in whether Carter’s First Amendment rights were violated.[22] Carter was convicted strictly by the words she sent through text messages and two short phone calls where she allegedly told Roy to get back into the car.[23] However, the only evidence that Carter told Roy to get back into his car was found in Carter’s texts to her friend.[24] The history of Carter’s texts repeatedly showed evidence of Carter lying and exaggerating in order to get attention from her friends.[25] Carter’s words therefore may not constitute “speech integral to criminal conduct” because she was doing nothing but exercising a right of free speech.[26] She did not engage in any non-speech conduct or assist Roy in getting anything to carry out his suicide.[27] The only “threat” was when Carter said, “you just need to do it Conrad or I’m gonna get you help.”[28] In the absence of any acts from Carter during Roy’s suicide, the First Amendment exception for speech integral to criminal conduct should not apply.[29]

On the other hand, according to Psychology Today, “social media facilitates a virtual form of interaction.”[30] Even though Carter strictly “threatened” Roy through her words in her text messages, her conduct while texting, “involved a high degree of likelihood that substantial harm [would] result to another.”[31] Just as the strikers in Giboney were engaging in acts of picketing to induce the distributor to not sell ice to non-union peddlers, here Carter was alleged to be engaging in an act of coercion––inducing Roy to get back into the car and commit suicide.[32] Carter’s speech therefore lacked protection because it was integral to committing involuntary manslaughter.[33]

Interactions that occur through social media make individuals feel connected.[34] Roy and Carter lived only about a hour away from one another, and in their two year relationship, they only met up five times.[35] According to Esquire magazine article, Carter’s relationship with Roy was described as a “fantasy,” and she had a hard time “apprehending reality.”[36] Even in the morning after Roy committed suicide, Carter texted Roy saying, “Conrad please answer me right now you’re scaring me.”[37] Roy had attempted to take his life on various other occasions and always texted Carter afterwards telling her what happened.[38] One of the greatest pleasures of an adolescent boy is to be worried over by a girl.[39] Roy would make suicide attempts and text Carter, “tonight’s the night.”[40] Carter was doing what she thought was “supporting” Roy and responded, “[y]ou said that last night and the night before.”[41] When Carter allegedly told Roy to get back in the car, it is difficult to know for sure whether she actually thought he was going to kill himself, or whether he was just seeking attention as she had sought attention from her friends.[42] Carter would seek attention by telling her friends that she was cutting herself, but there was no evidence that she was actually doing this.[43] Carter may have thought that Roy was telling her that he was going to hurt himself, as a way to garner attention as well.

Further details supporting that Carter’s relationship with Roy was Carter’s fantasy are seen through text messages to Roy that were direct quotes from the transcripts of the television show, Glee.[44] Lea Michele and Cory Monteith were an on-and-off screen couple.[45] Monteith died of an accidental overdose and the show Glee paid tribute to him.[46]

Due Process Violations

The second issue the Supreme Court should have addressed was whether the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment was violated.[55] The ruling by the SJC expanded the common law of involuntary manslaughter.[56] The issue with the ruling is that it fails to provide reasonably clear guidelines to prevent “arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement,” for future assisted or encouraged suicide cases.[57] Before the ruling in Carter, involuntary manslaughter cases always involved a defendant who was present.[58] Carter was not present during Roy’s suicide.[59] It was argued that it was a stretch to say she was present, when she was only “virtually” there.[60] On the other hand, it was argued that “words become weapons for both linguistic and psychological reasons” and Carter did not need to be present to help Roy obtain the portable water pump, drive his car to Kmart, and fill his car with fumes.[61] The SJC ruled that Carter’s words alone were enough to convict her of manslaughter.[62]

The issue arising from this ruling that should have been addressed by the Supreme Court is that an involuntary murder from “verbal conduct” was never defined in the SJC ruling or seen in any prior cases.[63] This leaves ambiguity in the standard future prosecutors and judges should use when determining whether language can result in criminal liability.[64] This lack of a standard is a major issue when 95 percent of teenagers reported they have access to a smartphone and 45 percent of them said they are online “almost constantly.”[65] Out of those teens who reported using social media, 59 percent have been bullied or harassed online and 16 percent of teens reported physical threats on social media.[66] After Carter, can a single statement be sufficiently “coercive” to constitute “wanton and reckless conduct?”[67] With such high levels of online cyberbullying, when do teens cross the line from advice to coercion? Should adolescents be incarcerated in overcrowded prisons from sending one message over social media or does it have to be frequent communication? A recent study showed that “technology, such as texting, causes a decline in reflective thought (analyzing and making judgments) and promotes rapid shallow thought that when used too frequently, can create moral and cognitive ‘shallowness.’”[68] For instance, many contestants on the popular television show, The Bachelor, receive many death threats and are attacked by fans on social media.[69] One contestant went on a Bachelor interview podcast and stated that he “went into a deep hole of sadness” after the showed aired and “didn’t want to leave [his] apartment because there were so many people out there that [he] had disappointed.”[70] This leaves more ambiguity as to whether hundreds of fans of the Bachelor could be held liable if the threats affect the Bachelor contestants in a way that causes actual harm or death. The Supreme Court should have reviewed this case to set guidelines on virtual verbal conduct from online threats and cyberbullying.

Conclusion

The current uncertainty that resulted from the Supreme Court denying the petition for certiorari is problematic because the combination of “mental illness, adolescent psychology, and social media” will undoubtedly lead to related cases in the future.[71] According to the World Health Organization, “[a]n estimated 10-20% of adolescents . . . experience mental health conditions.”[72] The combination of teens who suffer from mental health conditions and the teens who suffer from getting bullied on social media will only lead to more situations similar to Carter v. Massachusetts.[73] Recent studies and statistics show that feeling abused on social media is a feeling shared by almost half of users, and cases similar to this are bound to continue to come before the court until guidelines and new policies are addressed and implemented.[74] Therefore, the Supreme Court should have reviewed this case.

*Brittany Kouroupas, J.D., expected May 2022, The George Washington Law School. I would like to thank the staff of the Criminal Law Brief for giving me this opportunity and mentorship to write about a field of law I am passionate about.

[1] Petition for Writ of Certiorari at 3, Carter v. Massachusetts, 140 S. Ct. 910 (2020) (No. 19–62).

[2] Id.

[3] Id.

[4] Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at 5.

[5] Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at 3.

[6] Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at 4.

[7] Id.

[8] Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at 3, 5.

[9] Id.

[10] Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at 5.

[11] Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at 7.

[12] Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at 6.

[13] Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at i.

[14] See Carter v. Massachusetts, 140 S. Ct. 910 (2020).

[15] See Ryan Holmes, Is COVID-19 Social Media’s Levelling Up Moment?, FORBES (Apr, 24, 2020, 12:03 PM), https://www.forbes.com/sites/ryanholmes/2020/04/24/is-covid-19-social-medias-levelling-up-moment/.

[16] Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at 7.

[17] See Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at i.

[18] See Giboney v. Empire Storage & Ice, 336 U.S. 490, 498 (1949).

[19] Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at 9-10 (citing Giboney, 336 U.S. at 498).

[20] See Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at 3.

[21] About the Supreme Court, UNITED STATES COURTS, https://www.uscourts.gov/about-federal-courts/educational-resources/about-educational-outreach/activity-resources/about (last visited Sept. 18, 2020).

[22] Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at17.

[23] Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at 5.

[24] Id.

[25] Id.

[26] Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at 10.

[27] Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at 13.

[28] See Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at 9 n.2 (emphasis omitted).

[29] United States v. Osinger, 753 F.3d 939, 950-54 (9th Cir. 2014) (Watford, J., concurring).

[30] Liraz Margalit, The Psychology Behind Social Media Interactions: Why Is Digital Communication So Often Easier than Communicating Face-to-Face?, PSYCH. TODAY (Aug. 29, 2014), https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/behind-online-behavior/201408/the-psychology-behind-social-media-interactions.

[31] See Brief in Opposition at 19, Carter v. Massachusetts, 140 S. Ct. 910 (2020) (No.19–62).

[32] See Brief in Opposition, supra note 31, at 10 (citing Giboney v. Empire Storage & Ice, 336 U.S. 490, 498 (1949)).

[33] Brief in Opposition, supra note 31, at 10.

[34] See Margalit, supra note 30.

[35] See Jesse Barron, The Girl from Plainville, ESQUIRE (Oct. 1, 2017), https://classic.esquire.com/article/2017/10/1/the-girl-from-plainville.

[36] Id.

[37] Id.

[38] See id.

[39] See id.

[40] See Hayley Soen, The Messages Michelle Carter Sent to Her Boyfriend Before He Died, THE TAB (Sept. 2019), https://thetab.com/uk/2019/10/08/michelle-carter-texts-messages.

[41] Id.

[42] See Bob McGovern, Defense Rests Without Calling Michelle Carter in Texting Suicide Case, BOS. HERALD (Nov. 17, 2018), https://www.bostonherald.com/2017/06/13/defense-rests-without-calling-michelle-carter-in-texting-suicide-case/.

[43] Id.

[44] See Korin Miller, Michelle Carter’s Obsession with ‘Glee’ Actors Cory Monteith and Lea Michele, Explained, WOMEN’S HEALTH (July 12, 2019), https://www.womenshealthmag.com/life/a28379177/michelle-carter-cory-monteith-lea-michele-glee-obsession/.

[45] See id.

[46] See id.

[47] Id.

[48] Id.

[49] Id.

[50] See id.

[51] Id.

[52] See Bob McGovern, Involuntarily Intoxicated: Expert Witness Says Reaction to Antidepressant Left Michelle Carter Delusional, BOS. HERALD (Nov. 17, 2018), https://www.bostonherald.com/2017/06/13/involuntarily-intoxicated-expert-witness-says-reaction-to-antidepressant-left-michelle-carter-delusional/.

[53] Id.

[54] See id.

[55] See Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at i.

[56] Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at 24.

[57] McDonnell v. United States, 136 S.Ct. 2355, 2373 (2016).

[58] Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at 34.

[59] Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at 3.

[60] Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at 36.

[61] See Peg Streep, When Words are Weapons: 10 Responses Everyone Should Avoid, PSYCH. TODAY (Mar. 23, 2015), https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/tech-support/201503/when-words-are-weapons-10-responses-everyone-should-avoid.

[62] Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at 5.

[63] See Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at 36.

[64] See Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at 35.

[65] Monica Anderson & Jingjing Jiang, Teens, Social Media & Technology 2018, PEW RSCH. CTR. (May 31, 2018), https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/.

[66] Id.

[67] Petition for Writ of Certiorari, supra note 1, at 34.

[68] Wendy L. Patrick, When Words Are Deadly Weapons: Michelle Carter’s Conviction, PSYCH. TODAY (June 24, 2017), https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/why-bad-looks-good/201706/when-words-are-deadly-weapons-michelle-carter-s-conviction.

[69] See Blake Horstmann Says He Received ‘Lots of Death Threats’ After ‘Bachelor in Paradise,’ BACHELOR NATION (Sept. 24, 2019), https://bachelornation.com/2019/09/24/blake-horstmann-bachelor-in-paradise-death-threats/.

[70] Id.

[71] Reply Brief of Petitioner at 1, Carter v. Massachusetts, 140 S. Ct. 910 (2020) (No. 19–62).

[72] See Adolescent Mental Health, WORLD HEALTH ORG. (Sept. 28, 2020), https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health.

[73] Reply Brief of Petitioner, supra note 71, at 1.

[74] See Monica Anderson & Jingjing Jiang, Teens’ Social Media Habits and Experiences, PEW RSCH. CTR. (Nov. 28, 2018), https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/11/28/teens-social-media-habits-and-experiences/.

Image originally located on northjersey.com.